Steven Avery

Administrator

From the Tim Dunkin article:

A Defense of the Johannine Comma

Selling the Record Straight on I John 5:7-8

Timothy W. Dunkin

Revised, July 2010

With the gratefully accepted assistance of Steven Avery

https://web.archive.org/web/2014112...dytoanswer.net/bibleversions/commadefense.pdf

https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/11724872/a-defense-of-the-johannine-comma-study-to-answernet

Other scholars have likewise acknowledged that Cyprian cited the Comma. In the 19th century, Bennett observed that Cyprian quotes the Comma, and dismisses the argument that Cyprian was really presenting an allegorical interpretation of v. 8. 67 In more modern times, Elowsky, following Maynard, accepts that Cyprian genuinely cited the Comma, 68 and Gallicet likewise observes that Cyprian’s quotation of the Comma is difficult to doubt. 69 Pieper states the case exquisitely, when he noted,

Indeed, it seems fair to observe that those who comment on the matter, and who do not have a particular textual axe to grind, readily acknowledge that Cyprian really, truly did cite the Johannine Comma. It is only when the a priori prejudices of a writer interfere, that Cyprian’s quotation becomes “unlikely.” As an example of this, observe Sadler’s statement concerning the question of Cyprian’s citation,

Essentially, the argument Sadler is making is that, because we already “know” that the Comma didn’t appear until centuries after Cyprian, the very clear citation by Cyprian (which, on its merit alone, would be accepted “without the slightest doubt”) must therefore be an “interpolation.” Why? Because that’s what the “accepted” interpretation demands – evidence contrary to the Critical Text dogma of the inauthenticity of the Comma must be explained away and ignored. This sort of argumentation employed by modernistic textual critics is simple intellectual dishonesty. Instead of trying to “explain away” evidence, following Scrivener in accepting Cyprian’s citation of the Comma seems to be the best path to follow. Certainly, our interpretation of later evidences, both pro and contra the Comma, should begin from the virtually certain historical fact (as seen from Tertullian and Cyprian) that some manuscripts in use in the churches around 200-250 AD, whether Old Latin or the Greek from which the Old Latin was derived, had the heavenly witnesses in their texts.

At this point, we should make a comment about the corroborative nature of these witnesses in the Latin. From Tertullian onward, we see several early Latin witnesses to the Johannine Comma. These witnesses, all located in North Africa, do not exist in a vacuum. While Tertullian's witness from Against Praxeus is less clear, the fact that Cyprian clearly cites the verse, in the same geographical area, a mere five decades later, and makes it significantly more likely that Tertullian did, indeed, have this verse in mind when he used the particular language that he did. So likewise does the testimony of the Treatise on Rebaptism, mentioned earlier, the text of which also dates to this same general time frame and concerns a doctrinal controversy that took place in this specific geographical area. Cyprian is explicitly corroborated, further, by the fact that Fulgentius, the bishop of Ruspe in North Africa around the turn of the 6th century, both cited the verse in his own writings, and pointedly argued in his treatise against the Arians that Cyprian had specifically cited the Heavenly Witnesses. All of these evidences work together synergistically to shown that the Johannine Comma was recognized in the Latin Bibles of North Africa, both before and after the Vulgate revision was made.

67 James Bennett, The Theology of the Early Christian Church (1855), p. 94

http://books.google.com/books?id=Su4rAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA94

James Bennett (minister) - (1774-1862)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Bennett_(minister)

68 Joel C. Elowsky, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: New Testament, IVa, John 1-10, p. 359, note # 37

http://books.google.com/books?id=rW1ldBkoDY4C&pg=PA359

Joel Elowsky (b. 1963)

https://www.csl.edu/directory/joel-elowsky/

https://csl.academia.edu/JoelElowsky

https://sddlcms.org/media/files/Elowsky Biography.pdf

69 Ezio Gallicet, Cipriano di Cartagine: La Chiesa, p. 206, note # 12

https://www.abebooks.co.uk/Chiesa-Cipriano-Cartagine-Paoline-Editoriale-Libri/30206605694/bd

“Cipriano e la Bibbia: Fortis ac sublimis vox,” (1975) Cyprian Vol. 32 Issue 1: p. 58

La Chiesa: Sui cristiani caduti nella persecuzione ; L'unità della Chiesa

https://books.google.com/books?id=Q5VZuQ9L1nkC&pg=PA206

Ezio Gallicet (1931-2009)

http://www.idref.fr/050415956

https://data.bnf.fr/en/13528686/ezio_gallicet/

70 Franz August Otto Pieper, Christian Dogmatics, Trans. T. Engelder, Vol. 1, pp. 340-1; emphasis mine

https://books.google.com/books?id=I...xC8Ln0QGolZmTAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result

Franz August Otto Pieper (1852-1931)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_August_Otto_Pieper

Facebook - PureBible

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/605714079520485/?comment_id=606021242823102

Quotes from Pieper

https://eduodou.gitbooks.io/christi...inal_text_of_holy_scripture_and_the_tran.html

71 Micheal Ferrebee Sadler, The General Epistles of Ss. James, Peter, John, and Jude (1895), p. 252, note #1

http://books.google.com/books?id=Qp4XAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA252

Micheal Ferrebee Sadler (1819-1895)

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Sadler,_Michael_Ferrebee_(DNB00)

A Defense of the Johannine Comma

Selling the Record Straight on I John 5:7-8

Timothy W. Dunkin

Revised, July 2010

With the gratefully accepted assistance of Steven Avery

https://web.archive.org/web/2014112...dytoanswer.net/bibleversions/commadefense.pdf

https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/11724872/a-defense-of-the-johannine-comma-study-to-answernet

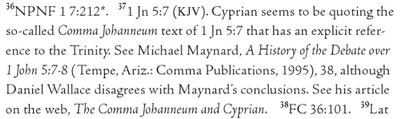

Other scholars have likewise acknowledged that Cyprian cited the Comma. In the 19th century, Bennett observed that Cyprian quotes the Comma, and dismisses the argument that Cyprian was really presenting an allegorical interpretation of v. 8. 67 In more modern times, Elowsky, following Maynard, accepts that Cyprian genuinely cited the Comma, 68 and Gallicet likewise observes that Cyprian’s quotation of the Comma is difficult to doubt. 69 Pieper states the case exquisitely, when he noted,

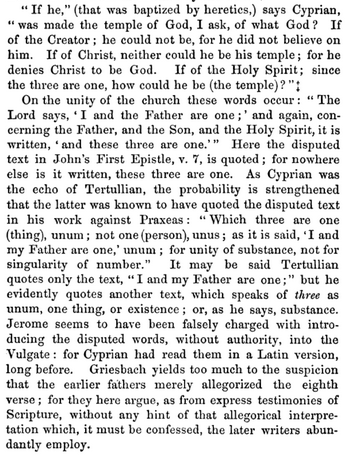

“Cyprian is quoting John 10:30. And he immediately adds: ‘Et iterum de Patre et Filio et Spiritu Sancto scriptum est: “Et tres unum sunt”’ (“and again it is written of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost: 'And the Three are One’”) Now, those who assert that Cyprian is here not quoting the words 1 John 5:7, are obliged to show that the words of Cyprian: ‘Et tres unum sunt’ applied to the three Persons of the Trinity, are found elsewhere in the Scriptures than 1 John 5. Griesbach counters that Cyprian is here not quoting from Scripture, but giving his own allegorical interpretation of the three witnesses on earth. "The Spirit, the water, and the blood; and these three agree in one." That will hardly do. Cyprian states distinctly that he is quoting Bible passages, not only in the words: ‘I and the Father are one,’ but also in the words: ‘And again it is written of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost.’ These are, in our opinion, the objective facts.”70

Indeed, it seems fair to observe that those who comment on the matter, and who do not have a particular textual axe to grind, readily acknowledge that Cyprian really, truly did cite the Johannine Comma. It is only when the a priori prejudices of a writer interfere, that Cyprian’s quotation becomes “unlikely.” As an example of this, observe Sadler’s statement concerning the question of Cyprian’s citation,

“If there had been evidence that the early MSS, and Fathers knew the text of the three heavenly witnesses, there would not have been the slightest doubt but that Cyprian here cites the original text; but the absence of all evidence for it till three centuries later shows that in Cyprian’s copy there must have been an interpolation...”71

Essentially, the argument Sadler is making is that, because we already “know” that the Comma didn’t appear until centuries after Cyprian, the very clear citation by Cyprian (which, on its merit alone, would be accepted “without the slightest doubt”) must therefore be an “interpolation.” Why? Because that’s what the “accepted” interpretation demands – evidence contrary to the Critical Text dogma of the inauthenticity of the Comma must be explained away and ignored. This sort of argumentation employed by modernistic textual critics is simple intellectual dishonesty. Instead of trying to “explain away” evidence, following Scrivener in accepting Cyprian’s citation of the Comma seems to be the best path to follow. Certainly, our interpretation of later evidences, both pro and contra the Comma, should begin from the virtually certain historical fact (as seen from Tertullian and Cyprian) that some manuscripts in use in the churches around 200-250 AD, whether Old Latin or the Greek from which the Old Latin was derived, had the heavenly witnesses in their texts.

At this point, we should make a comment about the corroborative nature of these witnesses in the Latin. From Tertullian onward, we see several early Latin witnesses to the Johannine Comma. These witnesses, all located in North Africa, do not exist in a vacuum. While Tertullian's witness from Against Praxeus is less clear, the fact that Cyprian clearly cites the verse, in the same geographical area, a mere five decades later, and makes it significantly more likely that Tertullian did, indeed, have this verse in mind when he used the particular language that he did. So likewise does the testimony of the Treatise on Rebaptism, mentioned earlier, the text of which also dates to this same general time frame and concerns a doctrinal controversy that took place in this specific geographical area. Cyprian is explicitly corroborated, further, by the fact that Fulgentius, the bishop of Ruspe in North Africa around the turn of the 6th century, both cited the verse in his own writings, and pointedly argued in his treatise against the Arians that Cyprian had specifically cited the Heavenly Witnesses. All of these evidences work together synergistically to shown that the Johannine Comma was recognized in the Latin Bibles of North Africa, both before and after the Vulgate revision was made.

67 James Bennett, The Theology of the Early Christian Church (1855), p. 94

http://books.google.com/books?id=Su4rAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA94

James Bennett (minister) - (1774-1862)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Bennett_(minister)

68 Joel C. Elowsky, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: New Testament, IVa, John 1-10, p. 359, note # 37

http://books.google.com/books?id=rW1ldBkoDY4C&pg=PA359

Joel Elowsky (b. 1963)

https://www.csl.edu/directory/joel-elowsky/

https://csl.academia.edu/JoelElowsky

https://sddlcms.org/media/files/Elowsky Biography.pdf

69 Ezio Gallicet, Cipriano di Cartagine: La Chiesa, p. 206, note # 12

https://www.abebooks.co.uk/Chiesa-Cipriano-Cartagine-Paoline-Editoriale-Libri/30206605694/bd

“Cipriano e la Bibbia: Fortis ac sublimis vox,” (1975) Cyprian Vol. 32 Issue 1: p. 58

La Chiesa: Sui cristiani caduti nella persecuzione ; L'unità della Chiesa

https://books.google.com/books?id=Q5VZuQ9L1nkC&pg=PA206

Ezio Gallicet (1931-2009)

http://www.idref.fr/050415956

https://data.bnf.fr/en/13528686/ezio_gallicet/

70 Franz August Otto Pieper, Christian Dogmatics, Trans. T. Engelder, Vol. 1, pp. 340-1; emphasis mine

https://books.google.com/books?id=I...xC8Ln0QGolZmTAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result

Franz August Otto Pieper (1852-1931)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_August_Otto_Pieper

Facebook - PureBible

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/605714079520485/?comment_id=606021242823102

Quotes from Pieper

https://eduodou.gitbooks.io/christi...inal_text_of_holy_scripture_and_the_tran.html

71 Micheal Ferrebee Sadler, The General Epistles of Ss. James, Peter, John, and Jude (1895), p. 252, note #1

http://books.google.com/books?id=Qp4XAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA252

Micheal Ferrebee Sadler (1819-1895)

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Sadler,_Michael_Ferrebee_(DNB00)

Last edited: