Steven Avery

Administrator

Brought over from Gavin to Facebook, now here.

Facebook - Gavin Basil McGrath

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/931123550312868/?comment_id=2713274472097758

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/931123550312868/?comment_id=2715399988551873

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/931123550312868/?comment_id=2718325508259321

7th paragraph

Thus the Trinitarian reading is also to be preferred for reasons of both general and specific immediate context in I John 5. The Trinitarian reading (I John 5:7,8) is to be preferred over the shorter reading on the basis that it alleviates a stylistic tension created in the Greek text without it. It is supported by ancient church Latin writers starting with Cyprian (258) and Priscillian (358), and continued in the Latin textual tradition, ultimately manifested in the Clementine Vulgate (1592).

The issue then arises as to why, if the Trinitarian reading (I John 5:7,8) is correct, is it absent in so many of the Byzantine Greek texts? The question of this omission’s origins is clearly speculative. On this basis, both advocates of the Burgonites’ Majority Text and neo-Alexandrian Texts e.g., the NU Text, consider they have a fatal argument for its authenticity. E.g., speaking for the NU Text Committee , Metzger claims, “if the passage were original, no good reason can be found to account for its omission, either accidentally or intentionally.141”

141 Metzger’s Textual Commentary, 1971, p. 716; 2nd ed., 1994, pp. 648.

Was this a deliberate omission? If so, probably some Trinitarian heretic deliberately expunged it.

Was this an accidental omission? If so, in order to consider this matter, it is first necessary to understand what the Greek text may have looked like on a copyist’s page. Here some difficulty arises since the exact nature of the Greek script was subject to some variation, both due to personal factors of handwriting, and trends at certain times. E.g., uncials (4th to 10th centuries) were in capital letters, whereas minuscules (9th to 16th centuries) are in lower case letters. Continuous script was also used at various times (i.e., no spaces between words, although some stylistic paper spaces might sometimes occur to indicate a new verse, or to try and right hand justify the page). When dealing with reconstructions of earlier, no longer existing Greek manuscripts, the exact appearance of the script is open to question. For my purposes, I have used a modern Greek script, which looks something like the original, and is close enough to what is required for the purposes of textual analysis. My script approximates that generally found in Greek NT’s published in modern times such as Scrivener’s Text. Sometimes a different script is required for textual analysis (see e.g., I Tim. 3:16142). Unless otherwise specified, I consider the script I use to be close enough to what is required, to make the basic point of textual analysis for my purposes.

In Greek it would have looked something like the following. The reading below first appears in a Greek script (which we find as a marginal reading in Minuscule 221,) and this would be something more like, though not identical with the unknown early handwritten copies; and then in the second instance this reading appears in the Greek with Anglicized letters. The practice we now use of lower case Greek letters in which the “s” or sigma inside a Greek word is “σ” but at the end of a Greek word is “ς”, does not appear in ancient unical manuscripts such as Codex Freerianus (W 032) where these always appear as a “C.” Therefore, for my purposes below I shall write the “eis” of the last line in the Greek lower case script not as “εις” but as “εισ”, bearing in mind that in the actual manuscript we are talking about this may well have been written as “EIC.” I will underline in the Greek script and highlight in bold in the Anglicized letters scripts, the sections I wish to draw particular attention to. With Greek in the round brackets “(),” and any added words that might go in italics in the square brackets “[],” following the AV’s translation as closely as possible (and only changing the Greek order once to accommodate the English rendering), the section more literally reads, “For (oti) three (treis) there are (eisin) the [ones] (oi) bearing record (marturountes) in (en) the (to) heaven (ourano), the (o) Father (Pater), the (o) Word (Logos), and (kai) the (to) Holy (Agion) Ghost (Pneuma): and (kai) these (outoi) the (oi) three (treis) are (eisi) one (en). And (Kai) three (treis) there are (eisin) the [ones] (oi) bearing witness (marturountes) in (en) the (te) earth (ge), the (to) spirit (Pneuma), and (kai) the (to) water (udor), and (kai) the (to) blood (aima): and (kai) the (oi) three (treis) in (eis) the (to) one (en) are (eisin). If

142 Burgon, J.W., The Revision Revised, John Murray, London, UK, 1883, pp. 98-105,424-7. (Though his style is convoluted, I agree with his basic conclusion on how the text should read, and consider that this is one of Burgon’s better textual analyses)

cxlvii

cxlvii(ei) the (ten) witness (marturian) ... etc. .

οτιτρειςεισινοιμαρτυρουντεςεντωουρανωοπατηρολογοςκαιτοΑγιονπνευμακαιουτοιοιτρειςενεισικαιτρειςεισινοιμαρτυρουντεςεντηγητοπνευμακαιτουδωρκαιτοαιμακαιοιτρειςειςτοενεισινειτηνμαρτυριανoti

treis eisin oi marturountes en toourano o pater o logos kai to Agion pneuma kai outoi oi treis en eisi kai treis eisin oi marturountes en te ge to pneuma kai to udor kai to aima kai oi treis eis to en eisin ei ten marturian

If an accidental omission, it seems that a copyist first wrote down, “oti treis eisin oi marturountes en t” (“For there are three that bear witness” with the first “t” of “the” in “the heaven,” 1 John 5:7), and then stopped for some kind of break. He possibly left a marker on the page pointing to the general area that he was up to. Either he remembered in his own mind, “I’m up to ‘treis eisin oi marturountes en’ with the first ‘t’ of the next word at the end of the line, just above the lines starting with ‘pneuma kai’ and ‘treis eis’ something;” or he said to a second copyist taking over, “I’m up to ‘treis eisin oi marturountes en’ with the first ‘t’ of the next word at the end of the line, just above the lines starting with ‘pneuma kai’ and ‘treis eis’ something.”

Upon resumption of copying out the text, returning to the right general area, the copyist’s eye saw on his original, the second ‘treis eisin oi marturountes en,’ his eye then looked down to see that this was just above the lines where without him realizing it, it was the second time ‘pneuma kai’ started a line, and the second time ‘treis eis’ something started the following line. His eye looked rapidly back to the end of the above line on his copyist’s page containing the words “oti treis eisin oi marturountes en t,” and seeing it ended with the “t” of “to” (from line 1, supra) and as he looked back, then remembering he was up to the end of a line, he then complicated his error as looked to the “to” (from line 4, supra), he copied “to pneuma kai to udor kai to aima kai oi treis eisto en eisin” etc., and so the text was inadvertently changed to, “For there are three that bear witness, the spirit, and the water and the blood: and these three agree in one.” If so, possibly the situation had been aggravated by the fact he was working in flickering candle light, or had a head cold, we simply do not know. Thus it was, that possibly by such an early accident in textual transmission history, in many Greek manuscripts the shorter ending later replaced the longer Trinitarian reading at 1 John 5:7,8.

On the one hand, textual analysis strongly supports the TR’s reading. It is also well attested to from a number of ancient church Latin writers, and was thus clearly accessible over the ages in Latin texts. But on the other hand, while found in the Greek as a marginal reading of Byzantine Minuscule 221, the textual support is generally from the Latin, and so manifests the lesser maxim, The Latin improves the Greek, being subject to the greater maxim, The Greek improves the Latin. Balancing out these competing considerations, on the system of rating textual readings A to E, supra, I would give the TR’s reading at 1 John 5:7,8 a low level “B” (in the range of 66% +/- 1%), i.e., the text of the TR is the correct reading and has a middling level of certainty.

This copyist’s error appears to have occurred quite early in the history of the text’s transmission, probably in the second century. That some manuscripts containing the correct and longer Trinitarian reading (1 John 5:7,8) survived, is evident in the Latin authorities which support this text. Thus a general witness of this text clearly that had reasonable accessibility was preserved over the centuries with the Latin. Then in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, this matter was brought to the attention of those masters of textual analysis who had been called and gifted by God to be neo-Byzantine textual analysts. It was spotted by them whether they were textual analysts of the Neo-Byzantine School through God’s common grace by racial gifts to Gentiles, such as the religiously apostate Gentile Christians of the Complutensian Bible; or whether they were textual analysts of the Neo-Byzantine School by special grace as elect vessels called and saved, and then made textual analyst “teachers” in his “body” of “the church” universal (Eph. 4:4,11; 5:31,32), such as Stephanus or Beza.

And so it was, that these gifted and learned men who composed our Received Text in the 16th and 17th centuries, and whose work represents a zenith of textual achievement in terms of producing an entire NT Received Text, not simply this or that verse as in former times, (the like of which shows up the neo-Alexandrian and Burgonite textual “scholars” to be truly second rate,) turned their learned eyes to the matter. And when these neo-Byzantines did so, seeking the guidance of God’s good Spirit, the deficiency in the representative Greek Byzantine manuscripts was thus spotted and remedied. Thus 1 John 5:7,8 was restored to its rightful place in the Received Text, and came to be translated in the Authorized Version. Praise God! His “word” “endureth for ever” (I Peter 2:25).

...

The Trinitarian God whose character is such that “there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one” (I John 5:7), manifested his character in the preservation of the NT Text through a system of triangulation. I.e., he evidently ordained that there be three witnesses: the Byzantine Greek, the Western Latin, and the ancient or mediaeval church Greek and Latin writers. Thus it follows that isolating just one of these three sources is insufficient.

==========================

typo - colienaeus

Upon scraping away centuries old ancient camel dung from the leaves containing 1 John 5:7,8, he found that they contained the shorter reading, rather than the longer reading of the Received Text. Dr. I.M.A. Botheringham said this new African text, found near Alexandria, was “proof positive” that the readings of the Received Text and Authorized Version are incorrect.

clxxii - clxxiii

Curious and deranged persons who have come after him, such as the Majority Text advocate, David Ottis Fuller, like to refer to “the magnificent Burgon,” and speak in a truly shocking and appalling derogatory tone, of Saint Jerome’s Latin Vulgate174. While we Protestants historically prefer the Greek Received Text to the Latin Vulgate for the purposes of NT translation, and while we Protestants want the Bible in our mother-tongue rather than in Latin, nevertheless, Jerome’s Latin Vulgate is accorded a place of proper respect. It is the single most distinguished representative from the Latin textual tradition, that forms one of the three closed classes of reputable sources with reasonable accessibility over time and through time, from which the NT Greek Text is properly composed. Majority Text advocates like Burgon and Fuller who deny the Latin Vulgate its due respect, therefore throw the baby out with the bathwater.

============

As one who recognizes the Providential protection of the NT Received Text in three closed classes, I consider the truly shocking and appallingly derogatory tone of Burgonite Majority Text advocates such as David Ottis Fuller against Saint Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, to not only constitute falsehood (9th commandment, Exod. 20:16), but also to enter the very realm of blasphemy itself (3rd commandment, Exod. 20:7; Rom. 2:24)178. While we do not regard him or his Latin Vulgate as infallible, certainly we Anglicans of the holy Reformed faith, look with general favour on that great and noble Biblical scholar, Saint Jerome (c. 342-420), whom the Book of Common Prayer (1662) remembers as a “Confessor and Doctor” of the church with a black letter day on 30 September. As Article 6 of the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles says of the OT canon, “the

clxxvi

other” OT Apocryphal “books (as Hierome [/ Jerome] saith) the Church doth ... not apply them to establish any doctrine.”

While we Protestants prefer the Greek Received Text to the Latin Vulgate for the purposes of NT translation, and while we Protestants want the Bible in our mother-tongue rather than in Latin, nevertheless, Jerome’s Latin Vulgate should be accorded a place of proper respect. It is the single most distinguished representative of the Latin textual tradition, that forms one of the three closed classes of reputable sources with reasonable accessibility over the centuries, from which the NT Greek Text is properly composed. It is the single most outstanding example of the Western Church’s Latin texts. It is one of Western Christendom’s great glories.

writers not father

raise the dead

Theodore Letis against Beza

Of importance for variants between the Received Text of the AV and Beza’s fifth edition of the Greek NT which was used critically by the AV translators, I have used Scrivener’s, The New Testament in the Original Greek According to the Text followed in the Authorized Version, Together with the Variants Adopted in the Revised Version (Cambridge University, 1881, Appendix, pp. 648-56). Despite its name, this work is not quite the AV’s TR, although it is very close to it (See Appendix 1 and issues raised in Appendix 2 of this commentary). Scrivener includes a list of variants in his Appendix (Ibid., pp. 655-6), saying, “The text of Beza 1598 has been left unchanged when the variant from it made in the Authorized Version is not countenanced by any earlier edition of the Greek. In the following places the Latin Vulgate appears to have been the authority adopted in preference to Beza.” Examples given include Scrivener’s “Beelzeboul” at Matt. 12:24,27 rather than the AV’s “Beelzebub.” In fact the AV translators would not have disputed the Greek at these passages, but for translation purposes they chose the Anglicized word derived from the Latin, rather than the Anglicized word derived from the Greek183. Such factors mean Scrivener does not properly understand the AV translators, and reminds us that his work must be used with some qualification and caution.

===========================

clxxxiiNT text, I would reply that the same is true for any of the manuscripts I cite in the section on the sources outside the closed class of sources e.g., the same would be true for the Alexandrian texts. They are nevertheless of some interest in considering the history of textual transmission outside the closed class of Greek and Latin NT sources. Tischendorf evidently found Dillmann’s Allophylic Ethiopic Version of some value in determining his neo-Alexandrian Text. I have generally referred to this Allophylian language translation when it is in Tischendorf’s textual apparatus. Like Tischendorf’s neo-Alexandrian text which it influenced, it is admittedly unreliable. My usage of this Ethiopic Version (Dillmann, 18th / 19th centuries), should also act to remind the reader of yet another problem with the neo-Alexandrian texts, namely, that their sources keep changing, depending on “the most recent discoveries.” Thus in Tischendorf’s day, the “discovery” of Dillmann’s Ethiopic Version put it at “the cutting edge” of neo-Alexandrian textual analysis. But as the years rolled by, and older “and therefore better” Ethiopic versions were “discovered,” Dillmann’s Ethiopic Version faded from neo-Alexandrian textual apparatuses. “Truth” it seems, is “a relative thing” for neo-Alexandrians, depending on “what manuscripts have been discovered.” Thus e.g., who is to say that manuscripts they now think so highly of, might not likewise suddenly become redundant if e.g., “new discoveries” of some older manuscripts are suddenly “discovered.” By contrast, we neo-Byzantines of the Received Text may from time to time discover new Byzantine Greek or Western Latin manuscripts. E.g., in 1879 the Byzantine Manuscript Sigma 042 (Codex Rossanensis, late 5th / 6th century), was discovered in Western Europe at the Cathedral sacristy of Rossano in southern Italy. But like other such discovered texts, they are acceptable to us to use because they conform to that which we already have had preserved for us over time and through time. They are not “new textual discoveries” in the sense of some “new text type,” but rediscoveries of a text type we already had and knew about. Thus they actually go to help show that which we always maintained. Their effect is to show how accurate e.g., Erasmus, Stephanus, and Beza were, to base the starting point of their Greek NT texts on representative Byzantine texts as determined from a relatively small sample of much later Byzantine Text manuscripts e.g., Erasmus’s Greek texts were no earlier than the 12th century.

The work on the Received text in the 16th and 17th centuries was really just a fine-tuning of Erasmus’s Greek NT text of (1516), which drew on a relatively small number of manuscripts, none of which were earlier than about the 12th century A.D. . The fact that the Textus Receptus can now be defended and determined through reference to much older Byzantine texts, such as e.g., Codex Rossanensis, from the late 5th or 6th century, in my opinion is a wonderful proof of how accurate the neo-Byzantines belief was in the preservation of the text over time and through time. In general, if not in every instance, we should reasonably expect to find texts much earlier than the 12th century which confirms for us the work of the 16th and 17th century neo-Byzantines working from these 12th century and later manuscripts. Thus these later discoveries of earlier Byzantine texts from e.g., the 9th century (Codex Cyprius), or 8th century (Codex Basilensis), or 6th century (Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus), or 5th century (Codex Freerianus in Matthew 1-28; Luke 8:13-24:53; and Codex Alexandrinus in the Gospels), or other centuries, is really exactly the sort of thing we always expected!

Moreover, neo-Byzantines of the 16th and 17th centuries knew that there were faulty texts circulating in ancient times. This was clear from e.g., Erasmus’s rejection of the Alexandrian Text dating to the 4th century in Codex B 02 (Codex Vaticanus), or Beza’s rejection of the Western Text dating to the 5th century in Codex D 05 (Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis), named after Beza who once owned it. Think of it! Neo-Byzantines of the 16th century preferred a 12th century Byzantine Text over a 4th century Alexandrian Txt or 5th century Western Text! The idea “the oldest known text is the best text” was clearly and wisely rejected by them.And time has proven them right! Thus the later discoveries of earlier corrupt texts from e.g., the 4th century with Codex Sinaticius and connected “rediscovery” of the Erasmus repudiated Codex Vaticanus, is once again the very sort of thing we always expected! There is thus stability to the Textus Receptus unmatched by the neo-Alexandrians. For we neo-Byzantines, truth is not relative, truth is absolute. The reader may therefore wish to ponder anew such things when he sees references to Dillmann’s Ethiopic Version, remembering how important this text was to the neo-Alexandrian Tischendorf, and how unimportant it is to later neo-Alexandrians

....

Also of value has been the text of the Burgonites, Maurice Robinson and William Pierpont. Even though the Majority Text is a count of all Greek manuscripts, not just the Byzantine Text ones (i.e., in Robinson & Pierpont’s K group selection taken from von Soden), because all others are a slim percentage well below five per cent of the total, in practice, the Majority Text equates the Byzantine Text184.

===========================

A Table of instance where Scrivener’s Text does not in fact represent the TR of the AV, is found in Appendix 1 of each volume.

===========================

NKJV good on debasement except calling it a Burgonite text

===========================

Luke Prologue - perfect understanding

===========================

Michael Swift -

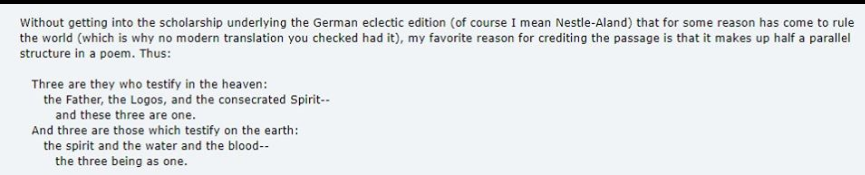

the theory that “Clunk the Interpolater” manage to write a beauifully Johannine verse that adds a Hebraic-style parallelism, matches perfectly, Johannine style, and fixes a bald Greek solecism when translated back from Latin!, and more like connecting the “testimony of God” in v. 9,

.. is the scribal-textual theory of seminarian Hortian village idiots, with a cold heart, not knowing the beauty of the Bible.

=====

Let me see if I can find the bookworm quote.

“But textual critics are like book worms - devoid of light and conscience, following blind instincts of their nature, they will make holes in the most sacred of books. The beauty, the harmony, and the poetry of the two verses would have melted the heart of any man who had s soul above parchment.”

Dublin Review (1881)

Charles Vincent Dolman

https://books.google.com/books?id=fwQJAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA141

Before going back to McGrath, this beautiful picture says a lot.

There is so much that Clunk the Interpolator could never do (btw, he had to add heaven and earth as well!. the whole thing is so absurd, Clunk (the interpolater) had to be more Johannine than John!

And he supposedly extrapolated the interpolation from allegoration of Cyprian! Bridges for sale! They will believe ANYTHING to deny the scripture..

Bridges for sale! They will believe ANYTHING to deny the scripture..

Question for Eastern Orthodox about 1 John 5:7

http://www.orthodoxchristianity.net...K1sIw79yWDqGa-5wVtoGzMyFT7p8h2RmTc#msg1132018

Look at the pic!

Facebook - Gavin Basil McGrath

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/931123550312868/?comment_id=2713274472097758

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/931123550312868/?comment_id=2715399988551873

https://www.facebook.com/groups/purebible/permalink/931123550312868/?comment_id=2718325508259321

Gavin Basil McGrath has a few pages on the heavenly witnesses, defending authenticity.

He also gives some special emphasis to the stylistic and harmony and internal elements.

A Textual Commentary on the Greek Received Text of the New Testament Being the Greek Text used in the AUTHORIZED VERSION also known as the KING JAMES VERSION (2012)

Gavin Basil McGrath

http://www.gavinmcgrathbooks.com/pdfs/1net1.pdf

p. cxl mentions Jay Green and the heavenly witnesses

Some refs at XCIX, the strong heavenly witnesses discussion really begins at CXL (140) to CXLVIII (148).

With some interesting general discussion right after, discussing how the learned men of the Reformation era skipped oddball corrupt mss.

My hope is to bring over a few quotes for discussion!

And more

Steven Avery

First, an important look at the general maxims:

(These are also in the recent studies on the verse order of Matthew 23:13-14).

=====================

There are two rules of neo-Byzantine textual analysis, found in two maxims, of relevance here. The master maxim is, The Greek improves the Latin; and the servant maxim is, The Latin improves the Greek. I.e., we neo-Byzantines always start with the representative Byzantine Greek text, which is maintained unless there is a clear and obvious textual problem with it, for The Greek improves the Latin. However, if it is clear that a textual problem in the Byzantine Greek can be remedied by a reconstruction of the Greek from the Latin, then the Latin reading may be adopted, for in such a context, The Latin improves the Greek. But in all this textual analysis, it is the Greek that is our primary focus, and the Latin is only brought in to assist what is an evident textual problem in the Greek, and only adopted if it resolves this Greek textual problem. Thus There are two rules of neo-Byzantine textual analysis, found in two maxims, of relevance here. The master maxim is, The Greek improves the Latin; and the servant maxim is, The Latin improves the Greek. I.e., we neo-Byzantines always start with the representative Byzantine Greek text, which is maintained unless there is a clear and obvious textual problem with it, for The Greek improves the Latin.

However, if it is clear that a textual problem in the Byzantine Greek can be remedied by a reconstruction of the Greek from the Latin, then the Latin reading may be adopted, for in such a context, The Latin improves the Greek. But in all this textual analysis, it is the Greek that is our primary focus, and the Latin is only brought in to assist what is an evident textual problem in the Greek, and only adopted if it resolves this Greek textual problem. Thus the lesser maxim, The Latin improves the Greek, is always subject to the overriding greater maxim, The Greek improves the Latin. the lesser maxim, The Latin improves the Greek, is always subject to the overriding greater maxim, The Greek improves the Latin.

=====================

Next, we will look at the seven paragraphs of stylistic, internal, harmony evidences. There is also some more later, like the homoeteleuton study.

Gavin Basil McGraath - p. cxliii

Significantly then, as it stands, the representative Byzantine Text presents a textual problem. We are told in the verse before 1 John 5:7,8, “to (the) Pneuma (Spirit) esti (he is) to (the) marturoun ([one] witnessing),” i.e., “the Spirit beareth witness” (1 John 5:6, AV); and then just after 1 John 5:7,8 reference is made to “e (the) marturia (witness) tou (-) Theou (of God),” i.e., “the witness of God” (I John 5:9, AV) which is Trinitarian in scope to “e (the) marturia (witness) tou (-) Theou (of God),” i.e., “the witness of God” (1 John 5:9, AV) which he has testified “Yiou (of Son) autou (of him)” i.e., “of his Son” (1 John 5:9, AV). So that the contextual scope is on God “the Spirit” (1 John 5:8), “God” the Father (1 John 5:11), and God the “Son” (1 John 5:9,11). This naturally results in the conclusion that I John 5:7,8 is referring to a Trinitarian witness by the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. But where is this expected witness in the representative Byzantine text reading?

This has a weakness in:

"God “the Spirit” (1 John 5:8)".

This weakens the strength of the claimed necessary Triad. The spirit in 1 John 5:8 is properly a small "s" and likely refers to the words of Jesus in Luke 23:46 and the John 10:30 text. Other interpretations are possible, but not Holy Spirit in 1 John 5:8.

1 John 5:6

This is he that came by water and blood, even Jesus Christ; not by water only, but by water and blood. And it is the Spirit that beareth witness, because the Spirit is truth.

The point may work well with v. 6.

================.

McGrath - 2nd sytlistic-internal-doctrinal-harmony paragraph (of 7)

"Furthermore, “the witness of men” (I John 5:9) means “the testimony of two men is true,” so that Christ can refer to the witness of himself and the Father (John 8:16-18). And indeed this passage at Deut. 19:15 that Christ refers to in John 8:16-18, further specifies as St. Paul says, “two or three witnesses” (II Cor. 13:1). Therefore, given the emphasis on the “Spirit” in I John 5:8, it is reasonable to include the Holy Ghost, with the consequence that if “the witness of God is greater” than “the witness of men” (I John 5:9), then the expectation must be that this is a Trinitarian witness of all three Divine Persons that is in focus. I.e., the representative Byzantine text has a textual problem in which it appears that something has been omitted that refers to a witness or testimony by the three Divine Persons of the Trinity; and the problem of omission so caused by the loss of this stylistic expectation constitutes a stylistic tension that can only be relieved by adopting the Trinitarian reading of what is largely the Latin textual tradition at I John 5:7,8. Indeed, this factor does not appear to have been lost on the Latin composers of the Clementine Vulgate, who evidently reached a similar conclusion, as well they might given that the textual argument is basically the same from the Greek or the Latin, and the textual remedy for this problem is found in the Latin textual tradition."

This may be accurate in a sense, but it is hampered by anachronistically referring again and again the "three Divine Persons". As a scholarly argument, it would have to be rethought and rewritten.

Gavin Basil McGrath

3rd paragraph combines three distinct Johannine stylistic arguments. Each one is solid and valid. I’ll number them, and the use of “Divine Persons” does not affect the Johannine stylistic points.

=======

I note that the Greek form in this Trinitarian reading found in the marginal reading of Byzantine Minuscule 221, whether understood as a Greek reconstruction through reference to the Latin, or as the preservation of the Greek form which is then further confirmed through reference to the Latin (a matter I shall not now discuss in further detail), is typically Johannine, both in writing style and theological emphasis.

1) E.g., the fact that the Second Person of the Trinity is called “the Word” (Greek o logos) (I John 5:7), bears an obvious similarity with “the Word” (Greek o logos) of this Apostle’s Gospel (John 1:1,14).

2) The statement of the three Divine Persons, “and these three are one” in which “one” is Greek “en” (I John 5:7), is strikingly similar to Christ’s statement about the two Divine Persons of the Father and the Son, “I and my Father are one” in which “one” is also Greek “en” (John 10:30), and shows a singular Supreme Being (God) with a plurality of Divine Persons.

3) So too the idea of “the Father” and “the Word” bearing “record” or witness (I John 5:7) is typically Johannine, for Christ says, “I am one that bear witness of myself, and the Father that sent me beareth witness of me” (John 8:18). And of the Holy Ghost, Christ says, “the Spirit of truth” “shall testify of me” (John 15:26). Indeed just before the Trinitarian reading (I John 5:7,8) we read, “it is the Spirit that beareth witness, because the Spirit is truth” (I John 5:6).

=======

A Textual Commentary on the Greek Received Text of the New Testament Being the Greek Text used in the AUTHORIZED VERSION also known as the KING JAMES VERSION (2012)

Gavin Basil McGrath

http://www.gavinmcgrathbooks.com/pdfs/1net1.pdf

cxliv-cxlv

Now we go the 4th paragraph on the stylistic issues, with a summary planned.

================

Moreover, the Apostle John frequently brings out a contrast between heaven and earth, saying, “he that cometh from above is above all; he that is of the earth is earthly, and speaketh of the earth: he that cometh from heaven is above all” (John 3:31). “Then came there a voice from heaven,” “Jesus answered and said,” “And I, if I be lifted up from the earth” (John 12:28,30,32). “These words spake Jesus, and lifted up his eyes to heaven, and said, Father,” “I have glorified thee on the earth” (John 17:1,4). Therefore, the Trinitarian reading which refers to the “three that bear record in heaven,” and the “three that bear witness in earth” (I John 5:7,8) seems typically Johannine.

Thus the Greek words, the Greek writing style, and the theological emphasis, all point to the Trinitarian reading (I John 5:7,8) being authentically Johannine.

================

The Johannine motif of heaven and earth is very real. It rings his authentic writing, and not "Clunk the Interpolater". The phrase "Trinitarian reading" works against the scholarly element, but the basic truth of Johannine style is 100% true.

Steven Avery

5th paragraph

(Note: Dabney has a good section)

The longer Trinitarian reading in the First Epistle of the Apostle John (I John 5:7,8), is also to be favoured as the correct reading for both general and specific reasons of immediate context.

In general terms, I John 5:1-8 works through a Trinitarian sequence in which “whosoever believeth that Jesus is the Christ” (Second Divine Person) is “born of God” (vs. 4), with reference to “the Son of God” (Second Divine Person, in connection with his relationship as “Son” to the First Divine Person) (vs. 5). Reference is then made to “the witness” of “the Spirit” (Third Divine Person) to “Jesus Christ” (Second Divine Person) (vs. 6). Thus the general context of I John 5:1-11 indicates a reference to “witness” by the other two Divine Persons, and this is what we then have in I John 5:7 when we read “there are three that bear record” (AV) or “three that bear witness” (NKJV) “in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost” (AV).

This one is a struggle to make clear.

6th paragraph

"In the specific context, we read in I John 5:9, “If we receive the witness of men, the witness of God is greater: for this is the witness of God which he hath testified of his Son.” Since “God” (First Divine Person) “hath testifieth of his Son” (Second Divine Person), this event in the past where “God” the Father “hath” testified of God the “Son,” seems to be an incongruous statement, unless one is first introduced to this notion that God the Father is witness, i.e., “there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one” (I John 5:7). Since the shorter ending reading of I John 5:7,8 makes no reference to God the Father as a witness, the longer Trinitarian reading makes more contextual sense."

This strong one is frequently given. The witness of God is a hanging chad without verse 7. The doctrinal additions hurt the argument, but basically this is very strong. Later I may show it in a few writers.

7th paragraph

Thus the Trinitarian reading is also to be preferred for reasons of both general and specific immediate context in I John 5. The Trinitarian reading (I John 5:7,8) is to be preferred over the shorter reading on the basis that it alleviates a stylistic tension created in the Greek text without it. It is supported by ancient church Latin writers starting with Cyprian (258) and Priscillian (358), and continued in the Latin textual tradition, ultimately manifested in the Clementine Vulgate (1592).

The issue then arises as to why, if the Trinitarian reading (I John 5:7,8) is correct, is it absent in so many of the Byzantine Greek texts? The question of this omission’s origins is clearly speculative. On this basis, both advocates of the Burgonites’ Majority Text and neo-Alexandrian Texts e.g., the NU Text, consider they have a fatal argument for its authenticity. E.g., speaking for the NU Text Committee , Metzger claims, “if the passage were original, no good reason can be found to account for its omission, either accidentally or intentionally.141”

141 Metzger’s Textual Commentary, 1971, p. 716; 2nd ed., 1994, pp. 648.

Was this a deliberate omission? If so, probably some Trinitarian heretic deliberately expunged it.

Was this an accidental omission? If so, in order to consider this matter, it is first necessary to understand what the Greek text may have looked like on a copyist’s page. Here some difficulty arises since the exact nature of the Greek script was subject to some variation, both due to personal factors of handwriting, and trends at certain times. E.g., uncials (4th to 10th centuries) were in capital letters, whereas minuscules (9th to 16th centuries) are in lower case letters. Continuous script was also used at various times (i.e., no spaces between words, although some stylistic paper spaces might sometimes occur to indicate a new verse, or to try and right hand justify the page). When dealing with reconstructions of earlier, no longer existing Greek manuscripts, the exact appearance of the script is open to question. For my purposes, I have used a modern Greek script, which looks something like the original, and is close enough to what is required for the purposes of textual analysis. My script approximates that generally found in Greek NT’s published in modern times such as Scrivener’s Text. Sometimes a different script is required for textual analysis (see e.g., I Tim. 3:16142). Unless otherwise specified, I consider the script I use to be close enough to what is required, to make the basic point of textual analysis for my purposes.

In Greek it would have looked something like the following. The reading below first appears in a Greek script (which we find as a marginal reading in Minuscule 221,) and this would be something more like, though not identical with the unknown early handwritten copies; and then in the second instance this reading appears in the Greek with Anglicized letters. The practice we now use of lower case Greek letters in which the “s” or sigma inside a Greek word is “σ” but at the end of a Greek word is “ς”, does not appear in ancient unical manuscripts such as Codex Freerianus (W 032) where these always appear as a “C.” Therefore, for my purposes below I shall write the “eis” of the last line in the Greek lower case script not as “εις” but as “εισ”, bearing in mind that in the actual manuscript we are talking about this may well have been written as “EIC.” I will underline in the Greek script and highlight in bold in the Anglicized letters scripts, the sections I wish to draw particular attention to. With Greek in the round brackets “(),” and any added words that might go in italics in the square brackets “[],” following the AV’s translation as closely as possible (and only changing the Greek order once to accommodate the English rendering), the section more literally reads, “For (oti) three (treis) there are (eisin) the [ones] (oi) bearing record (marturountes) in (en) the (to) heaven (ourano), the (o) Father (Pater), the (o) Word (Logos), and (kai) the (to) Holy (Agion) Ghost (Pneuma): and (kai) these (outoi) the (oi) three (treis) are (eisi) one (en). And (Kai) three (treis) there are (eisin) the [ones] (oi) bearing witness (marturountes) in (en) the (te) earth (ge), the (to) spirit (Pneuma), and (kai) the (to) water (udor), and (kai) the (to) blood (aima): and (kai) the (oi) three (treis) in (eis) the (to) one (en) are (eisin). If

142 Burgon, J.W., The Revision Revised, John Murray, London, UK, 1883, pp. 98-105,424-7. (Though his style is convoluted, I agree with his basic conclusion on how the text should read, and consider that this is one of Burgon’s better textual analyses)

cxlvii

cxlvii(ei) the (ten) witness (marturian) ... etc. .

οτιτρειςεισινοιμαρτυρουντεςεντωουρανωοπατηρολογοςκαιτοΑγιονπνευμακαιουτοιοιτρειςενεισικαιτρειςεισινοιμαρτυρουντεςεντηγητοπνευμακαιτουδωρκαιτοαιμακαιοιτρειςειςτοενεισινειτηνμαρτυριανoti

treis eisin oi marturountes en toourano o pater o logos kai to Agion pneuma kai outoi oi treis en eisi kai treis eisin oi marturountes en te ge to pneuma kai to udor kai to aima kai oi treis eis to en eisin ei ten marturian

If an accidental omission, it seems that a copyist first wrote down, “oti treis eisin oi marturountes en t” (“For there are three that bear witness” with the first “t” of “the” in “the heaven,” 1 John 5:7), and then stopped for some kind of break. He possibly left a marker on the page pointing to the general area that he was up to. Either he remembered in his own mind, “I’m up to ‘treis eisin oi marturountes en’ with the first ‘t’ of the next word at the end of the line, just above the lines starting with ‘pneuma kai’ and ‘treis eis’ something;” or he said to a second copyist taking over, “I’m up to ‘treis eisin oi marturountes en’ with the first ‘t’ of the next word at the end of the line, just above the lines starting with ‘pneuma kai’ and ‘treis eis’ something.”

Upon resumption of copying out the text, returning to the right general area, the copyist’s eye saw on his original, the second ‘treis eisin oi marturountes en,’ his eye then looked down to see that this was just above the lines where without him realizing it, it was the second time ‘pneuma kai’ started a line, and the second time ‘treis eis’ something started the following line. His eye looked rapidly back to the end of the above line on his copyist’s page containing the words “oti treis eisin oi marturountes en t,” and seeing it ended with the “t” of “to” (from line 1, supra) and as he looked back, then remembering he was up to the end of a line, he then complicated his error as looked to the “to” (from line 4, supra), he copied “to pneuma kai to udor kai to aima kai oi treis eisto en eisin” etc., and so the text was inadvertently changed to, “For there are three that bear witness, the spirit, and the water and the blood: and these three agree in one.” If so, possibly the situation had been aggravated by the fact he was working in flickering candle light, or had a head cold, we simply do not know. Thus it was, that possibly by such an early accident in textual transmission history, in many Greek manuscripts the shorter ending later replaced the longer Trinitarian reading at 1 John 5:7,8.

On the one hand, textual analysis strongly supports the TR’s reading. It is also well attested to from a number of ancient church Latin writers, and was thus clearly accessible over the ages in Latin texts. But on the other hand, while found in the Greek as a marginal reading of Byzantine Minuscule 221, the textual support is generally from the Latin, and so manifests the lesser maxim, The Latin improves the Greek, being subject to the greater maxim, The Greek improves the Latin. Balancing out these competing considerations, on the system of rating textual readings A to E, supra, I would give the TR’s reading at 1 John 5:7,8 a low level “B” (in the range of 66% +/- 1%), i.e., the text of the TR is the correct reading and has a middling level of certainty.

This copyist’s error appears to have occurred quite early in the history of the text’s transmission, probably in the second century. That some manuscripts containing the correct and longer Trinitarian reading (1 John 5:7,8) survived, is evident in the Latin authorities which support this text. Thus a general witness of this text clearly that had reasonable accessibility was preserved over the centuries with the Latin. Then in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, this matter was brought to the attention of those masters of textual analysis who had been called and gifted by God to be neo-Byzantine textual analysts. It was spotted by them whether they were textual analysts of the Neo-Byzantine School through God’s common grace by racial gifts to Gentiles, such as the religiously apostate Gentile Christians of the Complutensian Bible; or whether they were textual analysts of the Neo-Byzantine School by special grace as elect vessels called and saved, and then made textual analyst “teachers” in his “body” of “the church” universal (Eph. 4:4,11; 5:31,32), such as Stephanus or Beza.

And so it was, that these gifted and learned men who composed our Received Text in the 16th and 17th centuries, and whose work represents a zenith of textual achievement in terms of producing an entire NT Received Text, not simply this or that verse as in former times, (the like of which shows up the neo-Alexandrian and Burgonite textual “scholars” to be truly second rate,) turned their learned eyes to the matter. And when these neo-Byzantines did so, seeking the guidance of God’s good Spirit, the deficiency in the representative Greek Byzantine manuscripts was thus spotted and remedied. Thus 1 John 5:7,8 was restored to its rightful place in the Received Text, and came to be translated in the Authorized Version. Praise God! His “word” “endureth for ever” (I Peter 2:25).

...

The Trinitarian God whose character is such that “there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one” (I John 5:7), manifested his character in the preservation of the NT Text through a system of triangulation. I.e., he evidently ordained that there be three witnesses: the Byzantine Greek, the Western Latin, and the ancient or mediaeval church Greek and Latin writers. Thus it follows that isolating just one of these three sources is insufficient.

==========================

typo - colienaeus

Upon scraping away centuries old ancient camel dung from the leaves containing 1 John 5:7,8, he found that they contained the shorter reading, rather than the longer reading of the Received Text. Dr. I.M.A. Botheringham said this new African text, found near Alexandria, was “proof positive” that the readings of the Received Text and Authorized Version are incorrect.

clxxii - clxxiii

Curious and deranged persons who have come after him, such as the Majority Text advocate, David Ottis Fuller, like to refer to “the magnificent Burgon,” and speak in a truly shocking and appalling derogatory tone, of Saint Jerome’s Latin Vulgate174. While we Protestants historically prefer the Greek Received Text to the Latin Vulgate for the purposes of NT translation, and while we Protestants want the Bible in our mother-tongue rather than in Latin, nevertheless, Jerome’s Latin Vulgate is accorded a place of proper respect. It is the single most distinguished representative from the Latin textual tradition, that forms one of the three closed classes of reputable sources with reasonable accessibility over time and through time, from which the NT Greek Text is properly composed. Majority Text advocates like Burgon and Fuller who deny the Latin Vulgate its due respect, therefore throw the baby out with the bathwater.

============

As one who recognizes the Providential protection of the NT Received Text in three closed classes, I consider the truly shocking and appallingly derogatory tone of Burgonite Majority Text advocates such as David Ottis Fuller against Saint Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, to not only constitute falsehood (9th commandment, Exod. 20:16), but also to enter the very realm of blasphemy itself (3rd commandment, Exod. 20:7; Rom. 2:24)178. While we do not regard him or his Latin Vulgate as infallible, certainly we Anglicans of the holy Reformed faith, look with general favour on that great and noble Biblical scholar, Saint Jerome (c. 342-420), whom the Book of Common Prayer (1662) remembers as a “Confessor and Doctor” of the church with a black letter day on 30 September. As Article 6 of the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles says of the OT canon, “the

clxxvi

other” OT Apocryphal “books (as Hierome [/ Jerome] saith) the Church doth ... not apply them to establish any doctrine.”

While we Protestants prefer the Greek Received Text to the Latin Vulgate for the purposes of NT translation, and while we Protestants want the Bible in our mother-tongue rather than in Latin, nevertheless, Jerome’s Latin Vulgate should be accorded a place of proper respect. It is the single most distinguished representative of the Latin textual tradition, that forms one of the three closed classes of reputable sources with reasonable accessibility over the centuries, from which the NT Greek Text is properly composed. It is the single most outstanding example of the Western Church’s Latin texts. It is one of Western Christendom’s great glories.

writers not father

raise the dead

Theodore Letis against Beza

Of importance for variants between the Received Text of the AV and Beza’s fifth edition of the Greek NT which was used critically by the AV translators, I have used Scrivener’s, The New Testament in the Original Greek According to the Text followed in the Authorized Version, Together with the Variants Adopted in the Revised Version (Cambridge University, 1881, Appendix, pp. 648-56). Despite its name, this work is not quite the AV’s TR, although it is very close to it (See Appendix 1 and issues raised in Appendix 2 of this commentary). Scrivener includes a list of variants in his Appendix (Ibid., pp. 655-6), saying, “The text of Beza 1598 has been left unchanged when the variant from it made in the Authorized Version is not countenanced by any earlier edition of the Greek. In the following places the Latin Vulgate appears to have been the authority adopted in preference to Beza.” Examples given include Scrivener’s “Beelzeboul” at Matt. 12:24,27 rather than the AV’s “Beelzebub.” In fact the AV translators would not have disputed the Greek at these passages, but for translation purposes they chose the Anglicized word derived from the Latin, rather than the Anglicized word derived from the Greek183. Such factors mean Scrivener does not properly understand the AV translators, and reminds us that his work must be used with some qualification and caution.

===========================

clxxxiiNT text, I would reply that the same is true for any of the manuscripts I cite in the section on the sources outside the closed class of sources e.g., the same would be true for the Alexandrian texts. They are nevertheless of some interest in considering the history of textual transmission outside the closed class of Greek and Latin NT sources. Tischendorf evidently found Dillmann’s Allophylic Ethiopic Version of some value in determining his neo-Alexandrian Text. I have generally referred to this Allophylian language translation when it is in Tischendorf’s textual apparatus. Like Tischendorf’s neo-Alexandrian text which it influenced, it is admittedly unreliable. My usage of this Ethiopic Version (Dillmann, 18th / 19th centuries), should also act to remind the reader of yet another problem with the neo-Alexandrian texts, namely, that their sources keep changing, depending on “the most recent discoveries.” Thus in Tischendorf’s day, the “discovery” of Dillmann’s Ethiopic Version put it at “the cutting edge” of neo-Alexandrian textual analysis. But as the years rolled by, and older “and therefore better” Ethiopic versions were “discovered,” Dillmann’s Ethiopic Version faded from neo-Alexandrian textual apparatuses. “Truth” it seems, is “a relative thing” for neo-Alexandrians, depending on “what manuscripts have been discovered.” Thus e.g., who is to say that manuscripts they now think so highly of, might not likewise suddenly become redundant if e.g., “new discoveries” of some older manuscripts are suddenly “discovered.” By contrast, we neo-Byzantines of the Received Text may from time to time discover new Byzantine Greek or Western Latin manuscripts. E.g., in 1879 the Byzantine Manuscript Sigma 042 (Codex Rossanensis, late 5th / 6th century), was discovered in Western Europe at the Cathedral sacristy of Rossano in southern Italy. But like other such discovered texts, they are acceptable to us to use because they conform to that which we already have had preserved for us over time and through time. They are not “new textual discoveries” in the sense of some “new text type,” but rediscoveries of a text type we already had and knew about. Thus they actually go to help show that which we always maintained. Their effect is to show how accurate e.g., Erasmus, Stephanus, and Beza were, to base the starting point of their Greek NT texts on representative Byzantine texts as determined from a relatively small sample of much later Byzantine Text manuscripts e.g., Erasmus’s Greek texts were no earlier than the 12th century.

The work on the Received text in the 16th and 17th centuries was really just a fine-tuning of Erasmus’s Greek NT text of (1516), which drew on a relatively small number of manuscripts, none of which were earlier than about the 12th century A.D. . The fact that the Textus Receptus can now be defended and determined through reference to much older Byzantine texts, such as e.g., Codex Rossanensis, from the late 5th or 6th century, in my opinion is a wonderful proof of how accurate the neo-Byzantines belief was in the preservation of the text over time and through time. In general, if not in every instance, we should reasonably expect to find texts much earlier than the 12th century which confirms for us the work of the 16th and 17th century neo-Byzantines working from these 12th century and later manuscripts. Thus these later discoveries of earlier Byzantine texts from e.g., the 9th century (Codex Cyprius), or 8th century (Codex Basilensis), or 6th century (Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus), or 5th century (Codex Freerianus in Matthew 1-28; Luke 8:13-24:53; and Codex Alexandrinus in the Gospels), or other centuries, is really exactly the sort of thing we always expected!

Moreover, neo-Byzantines of the 16th and 17th centuries knew that there were faulty texts circulating in ancient times. This was clear from e.g., Erasmus’s rejection of the Alexandrian Text dating to the 4th century in Codex B 02 (Codex Vaticanus), or Beza’s rejection of the Western Text dating to the 5th century in Codex D 05 (Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis), named after Beza who once owned it. Think of it! Neo-Byzantines of the 16th century preferred a 12th century Byzantine Text over a 4th century Alexandrian Txt or 5th century Western Text! The idea “the oldest known text is the best text” was clearly and wisely rejected by them.And time has proven them right! Thus the later discoveries of earlier corrupt texts from e.g., the 4th century with Codex Sinaticius and connected “rediscovery” of the Erasmus repudiated Codex Vaticanus, is once again the very sort of thing we always expected! There is thus stability to the Textus Receptus unmatched by the neo-Alexandrians. For we neo-Byzantines, truth is not relative, truth is absolute. The reader may therefore wish to ponder anew such things when he sees references to Dillmann’s Ethiopic Version, remembering how important this text was to the neo-Alexandrian Tischendorf, and how unimportant it is to later neo-Alexandrians

....

Also of value has been the text of the Burgonites, Maurice Robinson and William Pierpont. Even though the Majority Text is a count of all Greek manuscripts, not just the Byzantine Text ones (i.e., in Robinson & Pierpont’s K group selection taken from von Soden), because all others are a slim percentage well below five per cent of the total, in practice, the Majority Text equates the Byzantine Text184.

===========================

A Table of instance where Scrivener’s Text does not in fact represent the TR of the AV, is found in Appendix 1 of each volume.

===========================

NKJV good on debasement except calling it a Burgonite text

===========================

Luke Prologue - perfect understanding

===========================

Michael Swift -

the theory that “Clunk the Interpolater” manage to write a beauifully Johannine verse that adds a Hebraic-style parallelism, matches perfectly, Johannine style, and fixes a bald Greek solecism when translated back from Latin!, and more like connecting the “testimony of God” in v. 9,

.. is the scribal-textual theory of seminarian Hortian village idiots, with a cold heart, not knowing the beauty of the Bible.

=====

Let me see if I can find the bookworm quote.

“But textual critics are like book worms - devoid of light and conscience, following blind instincts of their nature, they will make holes in the most sacred of books. The beauty, the harmony, and the poetry of the two verses would have melted the heart of any man who had s soul above parchment.”

Dublin Review (1881)

Charles Vincent Dolman

https://books.google.com/books?id=fwQJAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA141

Before going back to McGrath, this beautiful picture says a lot.

There is so much that Clunk the Interpolator could never do (btw, he had to add heaven and earth as well!. the whole thing is so absurd, Clunk (the interpolater) had to be more Johannine than John!

And he supposedly extrapolated the interpolation from allegoration of Cyprian!

Question for Eastern Orthodox about 1 John 5:7

http://www.orthodoxchristianity.net...K1sIw79yWDqGa-5wVtoGzMyFT7p8h2RmTc#msg1132018

Look at the pic!

Last edited: