Steven Avery

Administrator

Venantius Honorius Clementianus Fortunatus (c.530–c.600/609)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venantius_Fortunatus

... His later work shows familiarity with not only classical Latin poets such as Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Statius, and Martial, but also Christian poets, including Arator, Claudian, and Coelius Sedulius, and bears their influence. In addition, Fortunatus likely had some knowledge of the Greek language and the classical Greek writers and philosophers, as he makes reference to them and Greek words at times throughout his poetry and prose.

FORTUNATUS, VENANTIUS HONORIUS CLEMENTIANUS (530-609),

1911 Encyclopaedia Brittanica

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911...a/Fortunatus,_Venantius_Honorius_Clementianus

=======================================

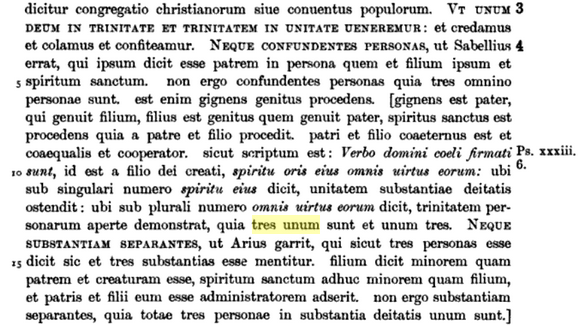

[Expositio Fidei Catholicae]

Texts and Studies: Contributions to Biblical and Patristic Literature Volume 2 Part 2 (1896 originally)

The Fortunatus Commentary

Joseph Armitage Robinson

https://books.google.com/books?id=iWYuAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA29

The Athanasian creed and its early commentaries (1896)

Andrew Ewbank Burn

https://archive.org/details/athanasiancreedi00burn/page/28/mode/2up

The Nicene and Apostles' Creeds: Their Literary History ; Together with an Account of the Growth and Reception of the Sermon on the Faith, Commonly Called "the Creed of St. Athanasius" (1875)

Charles Anthony Swainson

https://books.google.com/books?id=s75viscc3GEC&pg=PA317

============================================

Erasmus and the Middle Ages: The Historical Consciousness of a Christian Humanist (2001)

István Pieter Bejczy

https://books.google.com/books?id=MxLV1yVyT7sC&pg=PA43

The sixth-ccntury poet Vcnandus Fortunatus does not seem to have met with his approval either,33

33 Cf. Allen Ep. 2178:13 8.

CCEL

https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/hcc3.iii.xii.xvi.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venantius_Fortunatus

... His later work shows familiarity with not only classical Latin poets such as Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Statius, and Martial, but also Christian poets, including Arator, Claudian, and Coelius Sedulius, and bears their influence. In addition, Fortunatus likely had some knowledge of the Greek language and the classical Greek writers and philosophers, as he makes reference to them and Greek words at times throughout his poetry and prose.

FORTUNATUS, VENANTIUS HONORIUS CLEMENTIANUS (530-609),

1911 Encyclopaedia Brittanica

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911...a/Fortunatus,_Venantius_Honorius_Clementianus

=======================================

[Expositio Fidei Catholicae]

Texts and Studies: Contributions to Biblical and Patristic Literature Volume 2 Part 2 (1896 originally)

The Fortunatus Commentary

Joseph Armitage Robinson

https://books.google.com/books?id=iWYuAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA29

The Athanasian creed and its early commentaries (1896)

Andrew Ewbank Burn

https://archive.org/details/athanasiancreedi00burn/page/28/mode/2up

The Nicene and Apostles' Creeds: Their Literary History ; Together with an Account of the Growth and Reception of the Sermon on the Faith, Commonly Called "the Creed of St. Athanasius" (1875)

Charles Anthony Swainson

https://books.google.com/books?id=s75viscc3GEC&pg=PA317

============================================

Erasmus and the Middle Ages: The Historical Consciousness of a Christian Humanist (2001)

István Pieter Bejczy

https://books.google.com/books?id=MxLV1yVyT7sC&pg=PA43

The sixth-ccntury poet Vcnandus Fortunatus does not seem to have met with his approval either,33

33 Cf. Allen Ep. 2178:13 8.

CCEL

https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/hcc3.iii.xii.xvi.html

Last edited: