Steven Avery

Administrator

Sara Mazzarino

Report on the different inks used in Codex Sinaiticus and assessment of their condition

http://codexsinaiticus.org/en/project/conservation_ink.aspx

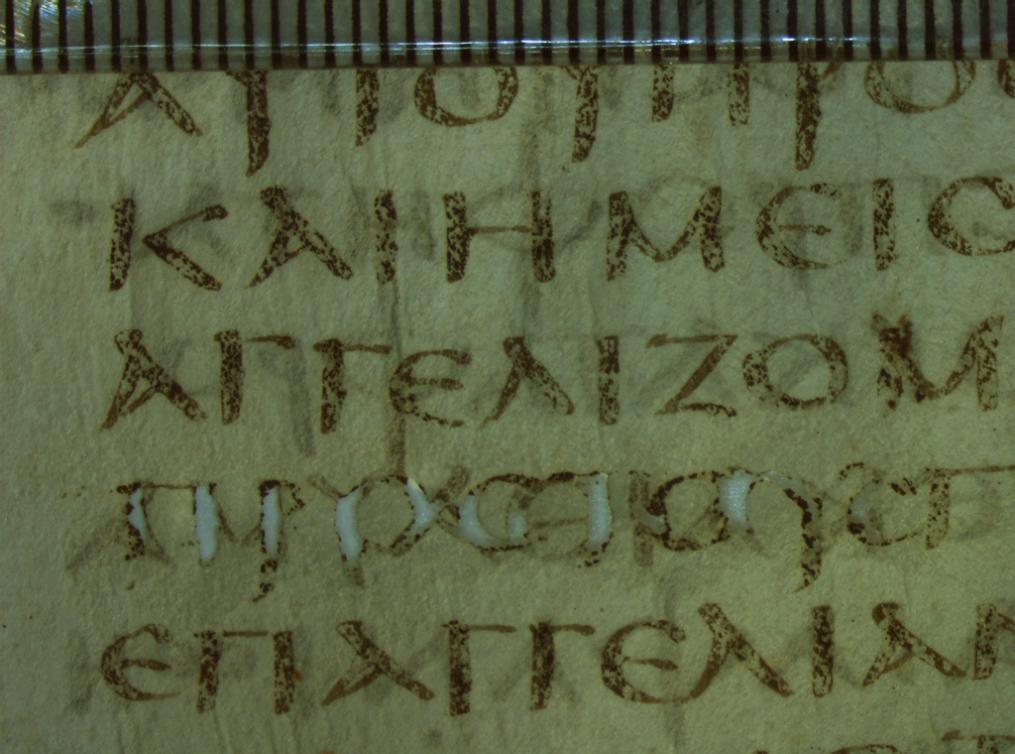

26. Major ink corrosion (Quire 86 f.7r, BL f.307r d11)

Correction .. Quire 87 - 4th column - 11th line

Acts, 13:9 - 13:38 library: BL folio: 307 scribe:

http://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manuscript.aspx?folioNo=7&lid=en&quireNo=87&side=r&zoomSlider=0

First, Sara's pic - this is the ONLY example of major ink corrosion

26. Major ink corrosion (Quire 86 f.7r, BL f.307r d11)

Correction - 26. Major ink corrosion (Quire 87 f.7r, BL f.307r d11)

Then the CSP

Wait, here there is no flaking visible.

In fact, it looks like an overwriting.

=============================

Many questions can be asked from these pictures, and from this page.

For now, we simply want to show one puzzle, and the resource involved, we had a helpful discussion with Sara Mazzarino.

Explanation

Flip side:

Emphasis added:

So the ink corrosion in the one spot given on the CSP was more likely erasing corrosion!

As children our erasures always weakened or cut t

Papyrus is tougher, but the principle is the same.

And why and when was there an erasure ???

Report on the different inks used in Codex Sinaiticus and assessment of their condition

http://codexsinaiticus.org/en/project/conservation_ink.aspx

26. Major ink corrosion (Quire 86 f.7r, BL f.307r d11)

Correction .. Quire 87 - 4th column - 11th line

Acts, 13:9 - 13:38 library: BL folio: 307 scribe:

http://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manuscript.aspx?folioNo=7&lid=en&quireNo=87&side=r&zoomSlider=0

2.1 Ink corrosion

Ink corrosion is the “burning” of an ink through the writing support. This degradation process may be determined by several factors such as; the ink’s composition, bad environmental conditions or characteristics of the writing support (nature of the raw materials, manufacturing process, concentration and homogeneity of the final product and so on). The condition assessment recorded the damages and distinguished between minor ink corrosion and major ink corrosion. These general categories were aimed to highlight areas in need of consolidation or treatment and identify areas to monitor carefully in the future. Minor ink corrosion causes pinprick-sized holes which have not locally weakened the parchment. Major ink corrosion concerns larger areas of text and creates a weakening of the parchment support.

Major Ink Corrosion

The portion of the Codex kept at the British Library shows very little major ink corrosion. The ink originally used by the scribes appears to be in very good condition, and it is not causing corrosion of the support in any part of the text.

An in-depth examination revealed that the only medium burning completely through the parchment support is the brown-black ink used for the second retracing of the main text.

Other inks, including those used for the corrections, have sometimes caused only minor etching of the parchment surface and have then flaked off.

The thinness of the parchment folia has sometimes facilitated the corrosion of the writing support. However, on its own, this characteristic does not determine the corrosion of the writing support. Indeed, some very thin leaves have not suffered from this damage while some other slightly thicker folia display losses caused by the ink degradation process.

The conservation conditions, the amount of handling, as well as a higher concentration or quantity of ink deposited on the parchment, may all be possible causes of damage. Furthermore, the way the writing support has been prepared can also determine the severity and the extent of such degradation.

As already mentioned, the quality of ink used for the retracing of the original text played a major role in the corrosion. This may be the result of its ingredients probably being not well balanced, thus allowing the development and catalysis of the degradation processes.

Major ink corrosion has sometimes caused weak areas: the most critical ones have been repaired by Cockerell.[41]

[41] D.C. COCKERELL, Condition, repair and binding of the manuscript, in H.J.M. MILNE, T.C. SKEAT, Scribes and correctors of the Codex Sinaiticus, London: British Museum 1938, pp.70-86.

First, Sara's pic - this is the ONLY example of major ink corrosion

26. Major ink corrosion (Quire 86 f.7r, BL f.307r d11)

Correction - 26. Major ink corrosion (Quire 87 f.7r, BL f.307r d11)

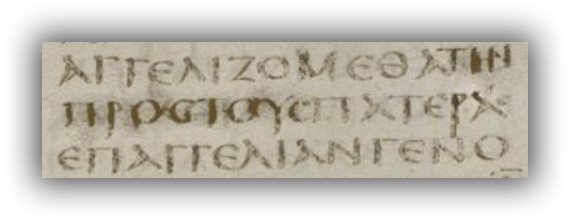

Then the CSP

Wait, here there is no flaking visible.

In fact, it looks like an overwriting.

=============================

Many questions can be asked from these pictures, and from this page.

For now, we simply want to show one puzzle, and the resource involved, we had a helpful discussion with Sara Mazzarino.

Explanation

Sara Mazzarino

I have checked the image: if you zoom in the image at the specific line d11 you will be able to see brown colored areas. The brown is given by the background, which was chosen in order to minimize the impact of losses in the support, when looking at the images.

If you compare the zoomed area with the detail pic on my report you will see that the brown areas of the first correspond to the white areas of the second. My aim was in fact to highlight the loss: for that reason I chose a white background as opposed to the brown.

So, yes, I can confirm there is corrosion and loss in that specific area.

Steven Avery

Thanks, Sara.

That was a great explanation, and after poking around both sides of the leaf I can see that it was totally eaten through.

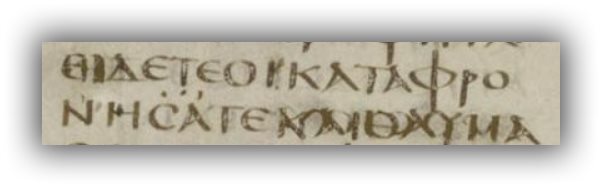

This leads to a second question, from the 1922 Kirsopp Lake black and white photos, on the CSNTM site, and you navigate to the two images (I am only showing recto)

http://www.csntm.org/Manuscript/View/GA_01|

CSNTM Image Id: 142050

CSNTM Image Name: GA_01_NT_0108a.jpg

Here we do not have the dark brown background. Yet it does not really appear to be eaten through. Is it possible that there was corrosion, e.g. in St. Petersburg, from 1911 to when Uncle Joe sold the ms. to Britain?

Continuing from before, I realize that working off the Kirsopp Lake photos (actually taken for the 1911 NT edition first ) might be a bit difficult. It is just a bit curious, maybe the ink wore through from 1912 to 2009?

On another topic, do you have any idea how to contact the image professional Laurence Pordes?

Any help on that contact would be appreciated! Thanks

(also discussed the tests that had been planned at Leipzig)

Flip side:

Emphasis added:

Sara Mazzarino

... However I do strongly believe that the corrosion was already there. In fact, the area of the specific word was previously erased and corrected. This made the parchment support even thinner than it already is. For this reason the ink affected the parchment in a more severe way creating holes.

I suspect that on KL images the holes are not clearly visible because he may have used a black background to improve contrast and legibility of the photographs. Or he may have retouched the negatives plates, again in order to improve legibility. Retouching of negatives was a very common practice and I wouldn't be surprise if this too was the case.

As far as the damage that may have happened from 1912 is concerned, well obviously nobody can guarantee that nothing has happened since. During the time of my studies on the Codex I compared KL images with CS at British Library and I didn't record evidences of changes sinces. To be fair, as previously mentioned, the negatives may have been retouched but we do not know that.

What I can certainly say is that the conservation conditions of CS are absolutely perfect in is current state.

So the ink corrosion in the one spot given on the CSP was more likely erasing corrosion!

As children our erasures always weakened or cut t

Papyrus is tougher, but the principle is the same.

And why and when was there an erasure ???

Last edited: