James Snapp #3 - Ten More Reasons Sinaiticus Was Not Made by Simonides

Saturday, March 25, 2017

Ten More Reasons Sinaiticus Was Not Made by Simonides

http://www.thetextofthegospels.com/2017/03/ten-more-reasons-sinaiticus-was-not.html

About four of this next group of 10 reasons from James are simply based on the fact that we do not know exactly what manuscripts were available at the monasteries of Mt. Athos and during the multi-year research of Benedict. Simonides specifically said that some unidentified manuscripts or editions were used in the collation and development process. And Benedict was well connected with a wide variety of sources available. David W. Daniels has done a lot of research into the background and views and motives of Benedict and this will be covered in depth in his two books, the first one of which is coming out about Jan. 8.

Is the 'World's Oldest Bible' A Fake?

When our little SART team discovered that Claromontanus (or its twin manuscript) was one of the manuscripts used in producing Sinaiticus, with a perfect homoeoteleuten match of sense-lines to Sinaiticus margin corrections, that simply put together one piece of the historical textual puzzle. Now that we have discovered that there is an edition of the Zosimas Moscow Bible available in the University of Glasgow library in Scotland, there is yet another source that can help with the Old Testament portion.

Even with the wonderful research addition of the Codex Sinaiticus Project, the establishment textual scholars have been to a large extent asleep. The SART team found the Uspensky material, and had it translated from Old Slovenian. Similarly the Russian scientist Morozov, who gave us teh astute ripping of the supposed authenticity of Sinaiticus, exposing the Tischendorf con. We discovered the colour tampering, simply by finding the Uspensky quote, and then looking carefully at the Codex Sinaiticus project, and viewing page by page, and then adding background and technical studies. We discovered the James Donaldson linguistic arguments, which have never been countered. We discovered the Claromontanus-->Sinaiticus homoeoteleutons.

Plus, many pieces of the historical puzzle are now in place. Benedict, Kallinikos and Simonides were in fact working together on manuscripts in Athos c. 1840, as documented in the 1895-1900 Spyridon Lambros catalog. Corroborating the most essential part of the Simonides account (the who and where, which could not be changed or fabricated historically.) Similarly, Kallinikos accused Tischendorf of colouring the manuscript, very early, when hardly anybody had seen the manuscript. Yet, we were able to confirm two years ago, simply by studying the Codex Sinaiticus Project and related materials, that the colouring had occurred, and the supple, flexible, barely-oxidized manuscript was in "phenomenally good condition." This, however, is not surprising for a manuscript that is less that 200 years old and was only handled in the first 20 years and then stashed, untouched, in library conditions.

What does James Snapp say about all of this in his presentation? ... nuttin, zilch, nada. His goal in this series is not to inform the readers about Sinaiticus, it is not even to counter the amazing evidences that this is a recent production. The goal of James is simply to be part of the textual criticism smoke-screen cover-up. Throw up some dust. And he mostly gives us a multiplication of nothings.

Meanwhile, the official group of textual scholars are asleep, working with their "deeply entrenched scholarship" that assumes the Tischendorf fabrication stories of accidentally finding a 4th century manuscript! "Conspiracy!" .. don't bother me with the facts!

Now, when looking at the arguments from James Snapp, we also have to conjecture about what what were the motives of Benedict and Simonides.

a) simply a creative and somewhat altruistic replica that might be traded for a printing press?

b) the possibility of passing off a new manuscript as authentically old?

c) conspiratorial (e.g. Jesuit) development of a companion ms. to Vaticanus that can work to try to dethrone the despised Textus Receptus, and the Reformation Bible editions around the world

Or there could be a hybrid combination of motives. Perhaps when the project began, the flux between fake and replica was simply left up in the air. Let's make it, and then decide.

And if there was conspiracy elements, they would definitely not be publicized. (Although hints may be dropped, like Fenton Hort talking of Tischendorf finding "rich materials", just a few years before Tischendorf "found" their companion-to-Vaticanus manuscript.

In the controversies of the 1860s, much of the attack against Simonides among his English opponents was that his story might not be totally on the up-and-up, perhaps his motives were not so Simon-pure, and were not so altruistic, perhaps he was involved in a planned forgery! The idea was that this would discredit his account (when actually it would simply give a slightly different spin on why the Simonieidos manuscript was made, and then stolen by Tischendorf.) In such a case, the essentials of the Simonides story would be true (as has been corroborated in many ways) but the details of the process would have some vanilla fudging.

Clearly, these gentlemen who tried to find little holes in the Simonides story to try to discredit the essentials (as James similarly tries today) were not very sharp cookies. Or they were embedded with the replacement Bible attempt.

All this is especially clear today when we know that Tischendorf only gave us tissues of lies, like the self-serving fabrication of saving parchment from fire! When all Tischendorf had done was mangle an intact manuscript, removing five full quires and three leaves more, and spirited them off to Leipzig as a test of passing off a nice clean, white, supple manuscript as if it were very ancient and heavily used.

If we weigh the historical veracity of Simonides to Tischendorf in regard to the manuscript, Simonides comes out way ahead, and is generally accurate. While Tischendorf is the charlatan, liar and thief. Tischendorf weaved a web of deception, and ultimately even forgery. First hiding the connection of the two sections. and then stashing them far away from each other away from prying scholars, and putting out a facsimile edition that hid the huge contrast between the Leipzig and St. Petersburg pages. Not once did Tischendorf ever acknowledge the simple truth that Leipzig is white parchment, reported and pretended it was yellow with age. (There was a similar deception which occurred in the 2011 facsimile edition, with everybody from the British Library and the American publishers going "what, we worry", nobody knowing why the pages were smoothed and tampered.)

As to trying to attack the Simonides account on quibble details about whether he was totally on the up-and-up, the truth was recently written by Charles van der Pool, well acquainted with the Greek Orthodox and the Sinaiticus history.

Lastly I find it somewhat comical that the charge against a forger was that he was convicted of forgery...that would seem to be more of a proof of his "credentials"

While Simonides was never convicted of forgery, the basic irony stands. Demonstrating or claiming that the motives of Simonides may have been different than what he shared in the 1860s controversies does absolute nothing to weaken the historical connection, and the essential elements of his account.

A third possibility is that of a tool of the Jesuit counter-Reformation-Bible attempts. There is solid evidence that a companion manuscript to Vaticanus would be a hoped-for find, as in the 1850s quote from Fenton Hort about Tischendorf finding "rich materials" to help along their planned competitor edition.

Or any combination of the three motives, the situation could have been in flux. The third, the counter Reformation Bible aspect, would involve a deliberate "conspiracy" aspect of the development of the Simoneidos text. Overall, it is rather easy to demonstrate that Simonides and his compatriots were involved in the production of the Sinaiticus manuscript, it is more involved to unravel the whole history.

Similarly it is unknown to what extent Codex Vaticanus, or facsimiles from the manuscript, were available before the real-time discoveries of 1844-45. Or Vaticanus information, notes or facsimiles were able to be used for certain elements like marginalia up to 1859. To give one example of the historical muddle, Tischendorf in his later writing c. 1870 said that he had made a facsimile edition of Vaticanus in the 1843 visit. Yet this contradicts the history that he had given earlier. And the Vatican offers no transparency in regard to their actions.

The simple truth is that Vaticanus readings could have been deliberately involved in the development of the manuscript.

In fact, there are various evidences of friendship or collusion between Simonides and Tischendorf over the years. They were called friends in some writings, although the Hermas tension of 1855 clearly put them at odds. The Tischendorf retraction of his lingistic accusations against Hermas, necessary to bring forth Sinaiticus, were kept hidden in a Latin background.

And even when the whole English journal disputes were over (putting aside for this purpose the Hermas and Barnabas linguistic expose by James Donaldson), Simonides, after a faked death report, quickly shows up (reported by Samuel Prideaux Tregelles! in contact with Rev Donald Owen) working in the Russian historical archives in St. Petersburg! St. Petersburg, where Tischendorf is now an esteemed scholar, since the Sinaiticus theft has been smoothed over. What an odd coincidence. Why would the Russians hire Simonides to work on "Historical Documents of Great Importance in Connection with Claims of the Russian Government”

the Russians hire Simonides to prepare historical documents after the 1867 fake obituary

https://www.purebibleforum.com/index.php/threads/a.176

In case you have difficulty reading between the lines, consider the idea of a quid pro quo between Tischendorf and Simonides. Simonides would stop giving Tischendorf a hard time about Sinaiticus, and he would have a good position in Russia. Maybe using some of his "particular set of skills." Remember, too, this was the time when there was still tension and claims and counter-claims between the St. Catherine's Monastery and the Russian administration, where even into the mid-1860s, the Tischendorf theft was considered and embarrasment that needed to be fixed.

We really do not know when cooperation between Simonides and Tischendorf began, even if it hit a rough spot with the Simonides publication of Hermas in 1855, before the similar Sinaiticus Hermas.

(11) Sinaiticus Has Rare Alexandrian Readings. ... The theory that anyone in the early 1800’s could happen to create all these agreements with Vaticanus is extremely unlikely. Most of them are agreements in error ...

(12) Sinaiticus Contains Many Non-Alexandrian Readings Which Are Singular or Almost Singular. A person creating a text in the early 1800’s based on a printed Greek Bible and a few manuscripts from Mount Athos would have neither the means nor the motive to create many readings found in Codex Sinaiticus. Such a person would occasionally make a mistake which at least one earlier copyist also made – but the appearance of so many singular or almost singular readings – not just mistakes – in Codex Sinaiticus puts very heavy strain on the theory that they were made by someone in the early 1800’s who was attempting to produce a gift for the Russian Emperor, because in such a setting there is nothing to provoke them.

These two are handled in the introduction. Plus, singular readings are to be expected in a sloppy transcription done by a teenager, as we know that Sinaiticus is full of blunders. They may have been some diction invovled as well, which would add to misspellings, itacisms and singular readings.

(13) Significant Parts of Sinaiticus Are Not Extant. Simonides claimed that he had visited Saint Catherine’s Monastery in 1852, and that he had seen his codex there, and that it was “much altered, having an older appearance than it ought to have. The dedication to the Emperor Nicholas, placed at the beginning of the book, had been removed.” However, much more of the Old Testament is not extant. No pages from Genesis were known to Tischendorf except the small fragment he found in 1853; the parts from Genesis 21-24 were either taken by Porphyry Uspensky, or discovered at Saint Catherine’s Monastery as part of the “New Finds” in 1975. The entire book of Exodus is gone; only chapters 20-22 of Leviticus are extant, and the surviving pages contain no more than ten chapters of Leviticus; only five of Deuteronomy’s chapters are attested on the surviving pages. Only two chapters of Joshua are extant, and no text from Judges was known to exist until fragments containing Judges 2:20 and Judges 4:7-11:2 were discovered among the “New Finds” in 1975. Such a museum of neglect and decay! And yet all that Simonides can say upon encountering his work in such condition is that it was much altered, and looked a little older than it should? And that the dedication-note at the front was missing??

There is a good reason why Simonides did not express dismay that what had been a complete Greek Bible in 1841 had been so thoroughly damaged that only a small fraction of the pages containing the Pentateuch had survived: he was unaware of it, having never seen the manuscript at Saint Catherine’s Monastery or anywhere else.

"No pages from Genesis were known to Tischendorf except..."

What silliness. James knows that Tischendorf lied about everything related to his visits. He knows that the Uspensky 1845 visit accounts shows the lying of the Tischendorf accounts. So why does James believe anything about what Tischendorf "knows"?

We can be quite sure from Uspensky that there was an extant full manuscript in 1844, but it was not the full OT. There is a very real possibility that Sinatiicus was never a complete manuscript. Playing with quire numbers would be an easy way to reduce the work load.

By contrast, the fact that the New Testament is complete, every verse, after 1500+ years of supposed heavy use, is quite suspicious:

"not disfigured by the smallest imaginable deficiency"

Almost as if the purpose of the whole endeavour was to supply a new New Testament text.

Similarly, we have the coincidence that a section that was specifically mentioned by Simonides as having his markings shows up in the New Finds or in cut-up fragments.

Similarly, the fact that the ending of Hermas, which presented a huge linguistic embarrassment for Tischendorf was thrown into a back room, is an evidence for Simonides involvement and more Tischendorf shenanigans.

Overall, we have more evidences supporting Simonides.

Did Simonides visit the monastery in 1852? Probably, but that would take a separate study. If he did, his report of mangling was sufficient, he may not remember, or want to get into, all the details. In fact, I don't remember that he ever specifically stated that the full OT was delivered.

At least we know that his various reports from the monastery (e.g. Tischendorf theft of 1844, the mangling of the manuscript, the colouring before 1859, the bumbling Greek of Tischendorf, etc.) were all accurate to a "T".

(14) Sinaiticus Has a Nearly Unique Text of the Book of Tobit. No resources at Mount Athos, or anywhere else in the early 1800’s, could supply the form of Greek text of Tobit that appears in Sinaiticus. As David Parker has noted, the text of Tobit in Sinaiticus agrees with the Old Latin translation of the book more closely than the usual Greek text does. In addition, the fragment Oxyrhynchus Papyri 1076, assigned to the 500’s, contains Tobit 2:2-5, and it agrees at some points with the text of Sinaiticus. (For example, both read καὶ ἐπορεύθη Τωβίας (“And Tobias went”) and ἔθνους, “nation,” (instead of γένους, “race”) in 2:3.)

This is simply suppositional conjectural ignorance from James Snapp. James has no idea what manuscirpts were in Mt. Athos, or available to Benedict, in 1840. He probably does not even know what is there in 2017. This is another multiplication of nothing.

And James also omits the Syriac connection (see below), probably on purpose since Simonides specifically alluded to an Old Syriac manuscript being used in the production:

"another very old Syriac Codex ..." (Elliott p. 56).

The quirkiness of Sinaiticus shows up everywhere. Why would a scriptorium have amateur bumbling scribes?

Why would the earliest extant Revelation be like a commentary? (As pointed out in a Juan Hernandez paper.)

Why are the editions of Hermas and Barnabas so late-Latinized that the learned James Donaldson said they could not be 300s AD, they had to be at least hundreds of years later?

Returning to Tobit, Does James even realize that Athos scholars like Simonides and Benedict could work with Latin and Syriac manuscripts? The Latin aspect was a big issue in the Hermas development where Simonides in one edition combined Greek and Latin manuscripts. So the big question arose: were non-extant Greek parts augmented by Latin sections?

So why is there any surprise that there could be Latinization element to Tobit? Or Syriac.

Now, James is actually echoing an 1863 argument from the Journal of Sacred Literature:

in the Old Testament, the text of Tobit and Judith, for example, are of quite a different recension—a recension still preserved principally in old Latin and old Syraic documents. How could this have been taken from the Moscow edition? or how could it be brought into it?

In fact, this argument, strangely enough, was simply taken from .. Tischendorf. who was always fishing for some way to claim authenticity and would never give a balanced presentation of the evidences.

Tischendorf - letter to Allgemeine Zeitung - Dec 22, 1862.

"in the Old Testament, the text of Tobit and Judith, for example, are of quite a different recension - a recension still preserved principally in old Latin and old Syraic documents. How could this have been taken from the Moscow edition? or how could it be brought into it?"

https://books.google.com/books?id=_bYRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA47

And Chris Pinto had gone into all variety of sources that were claimed by Simonides four years back!

Reporting The History of Codex Sinaiticus & Asking Questions Does Not Make a Conspiracy

https://www.worldviewweekend.com/ne...cus-asking-questions-does-not-make-conspiracy

In a letter written to his friend, Charles Stewart in 1860, Simonides described the manuscripts that were chosen by Benedict as the textual basis for the codex: “… the learned Benedict taking in his hands a copy of the Moscow edition of the Old and New Testament … collated it … with three only of the ancient copies, which he had long before annotated and corrected for another purpose and cleared their text by this collation from remarkable clerical errors, and again collated them with the edition of the Codex Alexandrinus, printed with uncial letters, and still further with another very old Syriac Codex …” (Letter of C. Simonides to Mr. Charles Stewart, as published in the Guardian, August 26, 1863, see Elliott, pp. 54-56*)

And I had responded to this argument in November 2014 (small changes made below):

New Testament Textual Criticism

https://www.facebook.com/groups/NTTextualCriticism/permalink/749871068433229/

When the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus shared scribes theories are developed, and the same scriptorium theories:

Is it pointed out that their texts of Tobit are totally different? Sinaiticus has a text that is akin to the longer Old Latin transmission lines:

"in the Old Testament, for example, the text of Tobit and Judith is of an entirely different recension, which is still preserved, particularly in old Latin and old Syriac documents." - Constantine Tischendorf, quoted in the Journal of Sacred Literature,and Biblical Record, Volume 3, 1863, p. 234

This is pointed out, usually emphasizing the Latin confluence, by the modern writers (who could consider the simpler explanation, that the medieval Latin and/or Syriac Codex influenced the Sinaiticus text) like Stuart D. Weeks of Durham University and Robert J. Littman of the University of Hawaii and Albert Pietersma of the University of Toronto.

This should be easier for them to see in Tobit, since that is one of the spots where you have "the tale of two manuscripts" the checkerboard, Tobit starts as a modern, pristine, no stains white parchment, (Codex Friderico-Augustanus, 1844 to Leipzig) and then in chapter 2 moves to the yellow with age and stains rest of Sinaiticus, of 1859 Tischendorf vintage. The picture is rather glaring.

Returning to the Greek ms. line, Vaticanus has the standard text that is throughout the Greek line, all uncials (Vaticanus, Alexandrinus and Vetenus are mentioned in NETS) and all cursives except 319. Sinaiticus, with 319, is oddball.

As I expected ms. 319 is from Mt. Athos (no surprise there

since Sinaiticus Hermas and Barnabas appear to be traced there as well, with medieval Latin influences, as pointed out by the learned Scottish scholar James Donaldson, 1831-1915) and Weeks says "Ms. 319 is properly Vatopedi 513 from Mt Athos; it dates from the eleventh century, and has ‘Long’ readings in 3.6-6.16." You can get the Greek font from:

since Sinaiticus Hermas and Barnabas appear to be traced there as well, with medieval Latin influences, as pointed out by the learned Scottish scholar James Donaldson, 1831-1915) and Weeks says "Ms. 319 is properly Vatopedi 513 from Mt Athos; it dates from the eleventh century, and has ‘Long’ readings in 3.6-6.16." You can get the Greek font from:

Some Neglected Texts of Tobit: the Third Greek Version (2006)

Stuart Weeks

https://www.academia.edu/…/Some_neglected_texts_of_Tobit_th…

Papyrus Oxvrhynchus 1594 joins the standard Tobit line, while 1076 is equated with the longer Latin line, except that the whole text is only five verses, making such an identification a bit of an extrapolation. The five Qumran fragments, four in Aramaic, one in Hebrew, do equate better to the Latin tradition (plus Sinaiticus, which however is often noted as unsatisfactory and corrupt and subject to many scribal errors) than the traditional Greek.

Ironically, the textual theorists properly use the opposite of lectio brevior praeferenda, the far more sensible longer reading, in favor of the longer (Hebrew and Latin) recension.

"Internal evidence also favors GII as the basis of GI; see, for example, 2.3 where one would be hard put to imagine how the fourteen Greek words of GI ("And he came and said, 'Father, one of our race has been strangled and thrown into the marketplace.' ") could possibly have been the source of the thirty-nine Greek words found in GII ("So Tobias went to seek some poor person of our kindred. And on his return he said, 'Father!' And I said, 'Here I am, my child.' Then in reply he said, 'Father, behold, one of our people has been murdered and thrown into the marketplace and now lies strangled there' "). One can readily see how the translator of G1 has condensed the narrative and the dialogue between Tobias and Tobit."

A New English Translation of the Septuagint

edited by Albert Pietersma, Benjamin G. Wright

https://books.google.com/books?id=--LQCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA457

Substitute "the scribe of the Alexandrian recension" for the "the translator of G1" for many NT applications.

NT Lectio brevior theory in essence is a special pleading and illogical application, designed to support the abbreviated Vaticanus-primacy text, and frequently the opposite of what is accepted in real textual analysis.

Steven Avery

==========================

Now, looking for contributors to Sinaiticus text, again note this:

Tobit ... The long version consists of the uncial Codex Sinaiticus (s) of the 4th century CE and its allied manuscripts, particularly the important minuscule, MS 319, from the Monastery of Mt. Athos, Greece, which contains the lacuna in Tobit 4:7-19.

Tobit: The Book of Tobit in Codex Sinaiticus

Robert J. Littman

https://books.google.com/books?id=M01vVo1dfUAC&pg=PR20

Hmmm... a Greek manuscript (GII from 3:6 to 6:16) that could be a fine exemplar used in the Tobit creation .. and from where? Mt. Athos! How could this be omitted by James?

Or, as Stuart Weeks puts it:

Tobit .. The textual problems posed by the book are notorious. The Qumran witnesses are too fragmentary to reconstruct a continuous text, and the principal witness to the earliest Greek version, Codex Sinaiticus, is frequently corrupt or defective in Tobit. This version may also be reconstructed to some extent, however, from ms. 319 (in part of the book) and from the very diverse Old Latin tradition.

A Deuteronomic Heritage in Tobit?

https://books.google.com/books?id=La7XsADlZjcC&pg=PA389

The inverse works: a combination of ms 319, the Old Latin, the Syriac codex and any other sources (did the Moscow Bible have Tobit?) were likely used in the Mt. Athos creation of their Tobit edition.

Now, Sinaiticus is still a scribal mess, with all sorts of omissions and misspellings. Perhaps sloppy work, including errors caused by dictation. This super-sloppy scribal component fits the 1840 understanding far better than the 4th century theory. The Simonides crew lacked some skills, and were overtaxed, they were not a professional scriptorium.

And there would have to be a combination of sources, but we know this was in fact the style of Simonides, and we are told very clearly that the development of the Simoneidos text was rather an involved procedure, with Benedict especially using a variety of sources. We can conjecture that Syriac and/or Latin sources are part of the process.

Granted, there still is a quesion about a small number of readings that align with an old semitic vorlage, akin to what we see in the Qumran fragments of Tobit, such as mss 4Q197. Words that do not have an exemplar known to be available in 1840. However, once again, we really do not know what was available to the gentlemen in Athos in their various Latin, Greek and Syriac manuscripts and resources. How many hundreds of manuscripts are on Athos today that have never been collated and published? And how many were there in 1840 that are either "gone manuscripts" or moved to another locale?

======================

This is one of a spots where the CFA is next to a regular sheet. Tischendorf took the full quires 35, 36, 47, 48, 49 . This 37 he only took a partial quire. (The ms. was pretty definitely bound when seen by Tischendorf in 1844, the fanciful loose leaves saved from the fire yarn was spun 15 years later.)

Tobit - Codex Friderico-Augustanus Q37f3v - Leipzig - colour - S1005-Y20R

http://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manuscript.aspx?folioNo=3&lid=en&quireNo=37&side=v&zoomSlider=0

Tobit - Sinaiticus - Q37f4r - British Library - colour S1010-Y10R

http://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manuscript.aspx?folioNo=4&lid=en&quireNo=37&side=r&zoomSlider=0

Picture available at:

Codex Sinaiticus Authenticity Research

Four Contiguous Points

http://www.sinaiticus.net/four contiguous points.html

So Tobit gives us a simple example of the pristine nature of the Leipzig, page, uncoloured against all manuscript science of oxidizing, yellowing and again. While the page at the British Library is (stained) yellow. Visual proof of the tampering, right in the pages of Tobit. About which James Snapp tells the readers ... nothing.

(15) A Copyist of Codex Sinaiticus Was Probably Familiar with Coptic. Scrivener explains the evidence for this in the Introduction to his Collation of Codex Sinaiticus: “It has also been remarked that no line in the Cod. Sinaiticus begins with any combination of letters which might not commence a Greek word, unless it be θμ in Matt. viii. 12; xxv. 30; John vi. 10; Acts xxi. 35; Apoc. vii. 4.” The letters θμ are capable of beginning words in Coptic, and this is probably why this exception was made; i.e., it was not an exception in Coptic.

Some of these Coptic evidences are unclear, as when James Keith Elliott refers to the "alleged Coptic mu". It would be nice to have some input from a true palaeographer, like Brent Nongbri. At any rate, let's just point out for now that Simonides was well acquainted with Egyptian writing, as part of his studies relating to hieroglyphics.

(16) One of the Later Correctors of Sinaiticus Had Unusual Handwriting. Several individuals – not just one or two – attempted to correct the text of Codex Sinaiticus. One corrector not only corrected the text, but occasionally corrected earlier correctors. This corrector’s handwriting was somewhat unusual; he added a small angular serif at the bottom end of the letters ρ, τ, υ, and φ.

Why James thinks that unusual handwriting is more a sign of antiquity than the 1800s is a puzzle. The handwriting of the Athos calligrapher, Dionysius, was the subject of note and humor "wretched, crabbed" in the controversy. This argument is a good example of the multiplication of nothings. There was plenty of time for corrections during the initial preparation by the Athos team (the Russico Rustlers, I call them) and also in the 20 years at the monastery.

Sidenote: In this regard, it would be helpful to really look closely at the writing of Uspensky to see how the original 1845 observations jive with the finals results in 1859.

(17) Constantine Simonides Was a Notorious Con Artist. It may be helpful, when evaluating Simonides’ claims about Codex Sinaiticus, to observe his other activities that he undertook at about the same time that he published those claims. In the same letter written by Simonides that was published in The Guardian on September 3, 1862, Simonides claimed that while at Saint Catherine’s Monastery in 1852, he had not only seen the codex, but also, among the manuscripts in the library, he found “the pastoral writings of Hermas, the Holy Gospel according to St. Matthew, and the disputed Epistles of Aristeas to Philoctetes (all written on Egyptian papyrus of the first century).” He had mentioned this manuscript earlier, in a book with the verbose title, Fac-Similes of Certain Portions of the Gospel of St. Matthew, and of the Epistles of Ss. James & Jude, Written on Papyrus in the First Century, and Preserved in the Egyptian Museum of Joseph Mayer, Esq. Liverpool.

In that book, Simonides claimed that in the antiquities collection of a resident of Liverpool, England named Joseph Mayer (a silversmith who was also an antiquities-collector), there were five papyrus fragments containing text from the Gospel of Matthew. After a long defense of the view that Matthew wrote his Gospel in Greek, rather than in Hebrew – and in this part of Simonides’ work there is some genuine erudition on display – Simonides described, complete with a transcription and notes about textual variants, this item. (The book even has pictures of the papyri.)

He claimed, for instance, that its text of Matthew 28:6 read “the Lord over death,” rather than simply “the Lord,” and he stated, “I prefer this text of Mayer’s codex over the others.” He also stated, “The 8th and 9th verses of the received version [i.e., the Textus Receptus] are extremely defective when compared with the text of Mayer’s’ codex.” Simonides belittled the usual readings of the passage [Matthew 28:9b] repeatedly, calling them incorrect and defective, “while Mayer’s codex gives the passage pure and correct, Καὶ ἰδοὺ ἐν τῷ πορεύεσθαι αὐτάς, ἀπήντησεν αὐταις ὁ Ἰησους λεγων Χαίρετε.”

As Simonides described the text of Matthew 19 on one of Mr. Mayer’s papyrus fragments, he remarked upon its text of verse 24: “ΚΑΛΩΝ is the reading I found in a most ancient manuscript of Matthew, preserved in the Monastery of Mount Sinai (Vide fac-simile No. 8, Plate I. p. 40.) This remarkable and precious manuscript, which I inspected on the spot, was written only 15 years after Matthew’s death, as appears from a statement appended by the copyist Hermodorus, one of the seventy disciples mentioned in the Gospel. It is written on Egyptian papyrus, an unquestionable token of the highest antiquity.”

Max Müller, in the journal The Athenaeum, in an article written on December 7, 1861, harshly reviewed the career of Simonides before declaring that “not one of these pretended documents is genuine.” Simonides, Müller wrote, had once visited Athens and had claimed that among the manuscripts at Mount Athos, he had found “an ancient Homer,” but when examined, this document “turned out to be a minutely accurate copy of Wolf’s edition of that poet, errata included!” That is, the supposedly ancient handwritten text was based on a printed edition of Homer.

Müller proceeded to list several more attempts by Simonides to defraud people with false antiquities. After Simonides had been repeatedly exposed as a charlatan, Müller contended, he “came soon afterward to Western Europe, bearing with him a goodly stock of rarities, and a reputation which the Cretans of the Apostolic times would have envied.” [The meaning of this remark is that the Cretans were notoriously dishonest, a la Titus 1:12, but Simonides’ reputation was far worse.]

Müller also mentioned that at a meeting of the Royal Society of Literature in May of 1853, Simonides presented what he claimed to be “four books of the Iliad from his “uncle Benedictus of Mount Athos,” an Egyptian Hieroglyphical Dictionary containing an exegesis of Egyptian history,” and “Chronicles of the Babylonians, in Cuneiform writing, with interlinear Greek” – but by the end of the day, it was pointed out that “the so-called cuneiform characters belonged to no recognized form of these writings, while the Greek letters suspiciously resembled badly or carelessly formed Phoenician characters.”

Müller’s summary of Simonides’ career as a huckster of forgeries stopped with his mention of “the explosion of the Uranius bubble.” By this phrase, Müller was referring to an earlier incident in which Simonides had offered to sell to the German government what he claimed to be an ancient palimpsest, containing the remains – 284 columns of text – of a work by a Greek historian named Uranius about the early history of Egypt, over which, it seemed, other compositions had been written in the 1100’s.

The members of the Academy of Berlin were persuaded, except for Alexander Humboldt, that it would be worthwhile to make a scholarly edition of this newfound text, and this task was undertaken by K. Wilhelm Dindorf. Eventually, however, a closer examination of the document, by Constantine Tischendorf and others, was undertaken, and with the help of chemicals and a microscope it became clear that the document was a fake (or half-fake – the forged ancient writing which, chronologically, should have had the medieval writing written over it, was above it instead). In 1856, Simonides was arrested, as reported on page 478 of the National Magazine. The case was not pursued in the courts; instead, Simonides left the country.

Tischendorf, in a letter written in December of 1862, responding to Simonides’ claim to have made Codex Sinaiticus, reminded his readers about that incident: “He contrived to outwit some of the most renowned German savants, until he was unmasked by myself.”

This should provide some idea of the nature of Simonides’ career, and how he worked: he created fraudulent manuscripts, using genuinely old – but blank or already used – papyrus or parchment on which to introduce his own work. He also occasionally acquired genuine manuscripts (including several Greek New Testament minuscules), in the hope that the affirmation of their genuineness would rub off on his own creations. He was guilty of fraud many times over.

After Tischendorf had helped expose the fraud that Simonides had come very close to pulling over on the Berlin Academy, Simonides may have afterwards harbored a strong desire to embarrass, or at least distract, Tischendorf. This may be why he later claimed that the most important manuscript Tischendorf ever encountered was actually the work of Simonides himself – a claim which, had it been true, would have drawn into question the accuracy of Tischendorf’s earlier appraisal of the Uranius palimpsest.

James is labouriosly demonstrating that Simonides had "a very particular set of skills" that could pull off the replica or forgery. Even today, some items like the Artemidorus papyrus are debated as to whether they were done by Simonides.

Charles van der Pool, knowledgeable about the orthodox and manuscripts, gave us a pithy comment on this style of argumentation:

The Apostolic Bible Polyglot Translator's Note

The Mount Sinai Manuscript of the Bible

http://www.apostolicbible.com/mountsinai.pdf

"Lastly I find it somewhat comical that the charge against a forger was that he was convicted of forgery...that would seem to be more of a proof of his 'credentials.'"

As for the specifics, James misses a lot. He does not even mention the Hermas of Simonides, that had the potential to torpedo the Sinaiticus enterprise. Nor does he mention the Barnabas of Simonides, which also fits perfectly with Simonides having helped prepare the Simoneidos manuscript at Sinai.

Nor does James mention the linguistic accusation by Tischendorf of the Simonides Hermas being from a later Latin. And then how Tischendorf retracted that accusation! (The accusation had to be withdrawn, since it would boomerang against Sinaiticus, as pointed out by the learned Scottish scholar James Donaldson.)

James gives the "pique" motive for Simonides. However, the historical corroboration of actually being in Athos and working on the manuscripts in Athos at precisely the right time, with Benedict and Kallinikos, belie that whole idea. The history being proven by the 1895-1900 catalogues of Spyridon Lambros. (This discovery, refuting the Kallinikos phantom theory, was one of a number of reasons why James Anson Farrer, in the 1907 Literary Forgeries, remained quite sympathetic to the idea that Simonides was a key part of the team that actually had written the manuscript.)

Similarly all the impossible manuscript and historical Tischendorf knowledge given by Simonides and Kallinikos. Including the 1844 theft of the 43 leaves, which we now can easily see as 100% factual, we even have the incriminating letter from Tischendorf to his wife. And, most dramatically, the colouring of the manuscirpt by Tischendorf, now visible, only after the 2009 Codex Sinaiticus Project used professional photography, skilled committees and placed the full manuscript online. (At the time they actually believed this was one harmonious ancient manuscript!) And then little things like the bumbling Greek of Tischendorf.

Similarly, Simonides knew there was no provenance for the manuscript, no catalogue entry (which would have ended the controversy quickly) because Simonides knew the monastery and he knew when they received the manuscript. The claim of "ancient catalogues":

ancient catalog at St. Catherine's Monastery?

https://www.purebibleforum.com/index.php/threads/a.103

that would prove Sinaiticus antiquity was simply one of the defensive lies that was quietly dropped.

This list of historical impossibilities goes on and on. In point of fact there are more evidences for friendship and cooperation between Tischendorf and Simonides (allowing the period of tension after the Hermas publication which was embarrassing to the forthcoming Sinaiticus) than of enmity. Even after all was said and done, Simonides had a faked death, and was working in the major Tischendorf stomping-ground, St. Petersburg, working on the Russian historical archives!

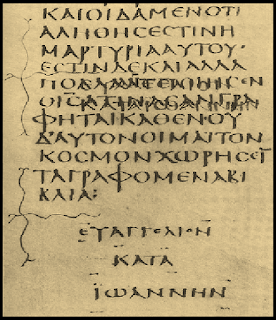

(18) The Last Verse of John Was Initially Omitted in Codex Sinaiticus. Although Tischendorf insisted that there was something weird about the final verse of John in Codex Sinaiticus, this was doubted by subsequent researchers, since even in photographs nothing seemed amiss. When the scholars Milne and Skeat, studying the manuscript in the early 1930’s for the British Museum, applied ultraviolet light to the passage, however, Tischendorf was vindicated: the copyist at this point finished the text at the end of 21:24, and drew his coronis, and wrote the closing-title of the book – and then he erased the closing-title (gently scraping away the ink) and the coronis, and the closing title. Then he added verse 25 immediately following verse 24, and remade a new coronis and closing-title. All this is as plain as day, as long as one has an ultraviolet light handy to examine the manuscript.

A thoughtful copyist could decide to reject the final verse, regarding it as a note by someone other than John. And his supervisor could overrule his overly meticulous decision. But Simonides would have had no reason to stop writing at the end of verse 24, add the coronis and closing-title, and then undo his work and remake the text with verse 25 included.

The insisting of Tischendorf, and the weird berating of Samuel Tregelles on this question, was itself quite suspicious. It is one of the many items that indicate that Tischendorf knew more about the actual production of the manuscript than he ever acknowledged. You get the sense that Tischendorf was familiar with the scribe and/or the supposed diorthote, and thus had "absolute confidence" (Gwynn) that the original Sinaiticus John ended at 24. Note that all of this internlinked with the strained Tischendorf desire to claim that a Sinaiticus scribe also worked on Vaticanus. (Such a connection would thus prove Sinaiticus antiquity. In the 1860s the scholars, especially the learned Hilgenfeld, even without knowing the details of the colouring and the parchment, and duped by the facsimile, argued that Sinaiticus was hundreds of years later than claimed by Tischendorf.)

Tischendorf in 1859 in his 7th edition specifically noted Codex 63 as omitting the John 21:25 verse, so he was well aware of the textual anomaly. In fact, this was corrected in 1864 by Scrivener, the manuscript had simply lost a leaf.

Tischendorf had such a vested interest in wanting this verse out of the Bible that he even omitted it (against thousands of manuscripts and many church writer citations) in his 1869 Greek New Testament edition! All very strange.

Everything about the ending of John 21 is simply suspicious, strongly indicating that Tischendorf knew more about the production of the manuscript than he let on, and this was the reason for his "absolute confidence". His omitting the verse from his Greek New Testament was just one of many indications that the man was a charlatan and unbalanced.

Tischendorf ... has gone so far as to adopt the extreme measure of striking the verse out of the text, in face of the concurrent testimony borne to it by countless patristic authorities, all versions and all manuscripts, cursive and uncial alike, including (on prima facie view) his own, then recently discovered, Codex Sinaiticus (X).

Hermethea - p. 374 (1893)

John Gwynn

https://books.google.com/books?id=VCsMAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA374

it is quoted without the least misgiving by a long array ot Patristic writers from Origen (who alleges it five times over) and Pamphilus downwards; and it is exactly in St. John’s simple manner to assert broadly that which cannot be true to the letter, leaving its necessary limitation to the common sense of the reader {see John vii. 39 ; 1 John iii. 9).- Scrivener, Full Collation p.LIX

In general, the copyists of Sinaiticus were rarely doing the original manuscirpt in a "thoughtful" manner. They blundered everywhere. As for mind-reading the production and thinking of Simonides, Benedict and other people working on the manuscript, that once again means little.

Yet even if Tischendorf was somehow simply sincerely mistaken, there is no reason why a bumbling Simonides, or his compatriot, might not simply err, miss a verse, and make the correction. Sinaiticus is filled up with scribal errors.

(19) The Lettering on Some Pages of Sinaiticus Has Been Reinforced. On page after page, the lettering that was first written on the page has been reinforced; that is, someone else has written the same letters over them, so as to ensure the legibility of what was once faded. The first page of Isaiah is a good example. This reinforcement was not undertaken mechanically, but thoughtfully; the reinforcer did not reinforce letters and words that he considered mistakes; he introduced corrections, such as in 1:6, where the reading καιφαλης is replaced by κεφαλης. Inasmuch as it is highly unlikely that the writing of a manuscript made in 1841 would be so faded that it would need to be reinforced within a few years, this weighs heavily against Simonides’ story.

Answered on BVDB

https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/bib...-answers-to-the-james-snapp-t6282.html#p80277

Isaiah 1 is an unusual page, with wild markings on top, and it can not be given as a "good example" without many additional pages also mentioned. By itself it is selective observation.

https://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manuscri ... omSlider=5

If there is reinforcement, then we should easily be able to show letters where the underwriting was not covered.

And on verse 1:6, you may have erasure, and a simple correction.

And that correction can be by the original scribe, or a reviewer the same day.

And weak ink is common, and can occasion immediate retouching, not necessarily hundreds of years later.

If James has a scholarly source for the claim that this page had a major reinforcement, covering large swaths of the page, hundreds of years after the manuscript was produced, then he should give the specific reference.

If he wants to simply claim his own observation, then where is the underwriting visible?

In the big picture, as an argument this is a fallacy of selective observation. In fact, the same can be said of the whole approach of James Snapp. Major in the minors, and totally ignore elephants in the living room.

There are ink and parchment anomalies everywhere on Sinaiticus, that do not match a supposed 1650+ years of heavy use. There is ink that is far too strong and clear, with virtually no acidic action on the parchment. We have pages on the anomalies on the Facebook Sinaiticus forum and on the PureBibleForum. We have the related puzzle of why Tischendorf trimmed the manuscript, eliminating notes.

We have the total refutation of the Tischendorf account once you read Uspensky's research on the white parchment manuscript in 1845. The New Testament was well known to both men, it was not hidden till 1859. Tischendorf mangled the manuscript, and this was reported accurately by Kallinikos.

Neither England nor Leipzig have had ANY chemical analysis of parchment or ink. When it analysis was planned in Leipzig in 2015, to be done by the world-class materials testing BAM group from Berlin, the plans were simply cancelled.

If you simply do a section with a weak ink or pen, it may need reinforcement. Sometimes I reinforce my own writing, if I used a mediocre pen, five minutes later. Thus the small amounts of reinforcement in Sinaiticus mean little. (The reports of Sinaiticus reinforcement are not consistent.)

James Snapp does not mention the ultra-supple "phenomenally good condition" (Helen Shenton, British Library) of the parchment and ink, simply because it essentially proves that the manuscript is not from antiquity. The Russian scientist Morozov pegged this right away, when he was able to actually see the manuscript in St. Petersburg. He essentially laughed at the claim that this was 1500+ years old, with lots of ongoing use during those years.

(20) Pages from Near the End of the Shepherd of Hermas in Codex Sinaiticus Are Extant.

When Simonides wrote his letter for The Guardian in 1862, he very clearly stated he concluded it with “the first part of the pastoral writings of Hermas,” but his work then ended “because the supply of parchment ran short.” Such a description plausibly interlocked with what one could discern at the time about the contents of Codex Sinaiticus by reading Tischendorf’s description of it. At the time, only the first 31 chapters of the text of Hermas were known to be extant in Codex Sinaiticus; that is all that Tischendorf had recovered from Saint Catherine’s Monastery. However, in 1975, when the “New Finds” were discovered, they included damaged pages from Hermas – to be specific, from chapters 65-68 and chapters 91-95. The Shepherd of Hermas has a total of 114 chapters. In no sensible way can Simonides’ statement that he wrote “the first part” of Hermas and stopped there be interlocked with the existence of pages containing the 95th of its 114 short chapters.

The clear and incriminating implication of this evidence is that Simonides’ report about how he produced the codex, including the prominent detail that he wrote the first part of Hermas but stopped there because he ran out of parchment, was shaped by his awareness of Tischendorf’s description of the codex, which stated that there was no text of Hermas extant after that point. If Simonides had actually written the codex, he would have said something to the effect that a large part of his work was missing.

Simonides and Kallinikos did say that the manuscript had been mangled and taken apart by Tischendorf.

As for Hermas, the simplest explanation is that Simonides, like many, had a tendency to say what was convenient. Not trying to be too contrary to the English opposition, he fudged elements of the story.Especially as the Brits listening to his story at times accused him of having made a forgery, not a replica, and that was not his purpose.

The Hermas New Finds discovery is especially interesting as that was the most embarrassing section of the 1844 Simoneidos document. Tischendorf wanted the Hermas and Barnabas discovery (they had already been reported by Uspensky and he writes as if the Hermas was complete in 1845), but the linguistic issues that came out around 1856 might torpedo the whole enterprise. Tischendorf accused the Hermas of Simonides of having later Latin elements. Then he found it the better discretion to quietly retract the accusation, in Latin, in a confusing section. James Donaldson said that this accusation also applies to the Sinaiticus Hermas. And, my conjecture is that it applies to the later parts of Sinaiticus (which Donaldson did not see.) Thus, Tischendorf limited the Sinaiticus Hermas damage by dumping much of the document in the dump room.

As a sidenote, it should be mentioned that in 1859 Simonides, in his biography, was intent on using the supposed antiquity of Sinaiticus (not yet named) as a wedge to claim antiquity for documents he was trying to sell in England. If such a nice parchment document actually dates to the first centuries, then you should surely accept these documents here, even though they don't really look and feel that old. Simonides was being practical, using the situation.

More evidence against the plausibility of Simonides’ story could be accumulated: indications that the copyists of Sinaiticus at least occasionally wrote from dictation, and the existence of textual variants (in Matthew 13:54, Acts 8:5, and First Maccabees 14:5) which suggest that a copyist was working at or near Caesarea, and the remarkable similarity between the design of the coronis applied by Scribe D at the end of Tobit and after Mark 16:8 in Sinaiticus, and the design of the coronis at the end of Deuteronomy in Codex Vaticanus, and the drastic shift in the text’s quality in Revelation, and more. But enough is enough.

As I explained above, the sloppy work of the Russico Rustlers fits perfectly with some of the work being by dictation. The Caesarea element is simply a somewhat strained theory, e.g. Ropes had a different take on the Acts variant than Hardy. We could look at it more, if James wants to really give it aas an argument. As for a coronis similarity with Codex Vaticanus, remember than Tischendorf saw (and even claimed in 1870 to have made a facsimile) Vaticanus and this design info could have easily transported to Sinaiticus by 1859, in varous vectors of transmission (similar to the Acts sections which we discussed above.) The text of Revelation really makes no sense for a 300s copy, Juan Hernandez notes similarities to later commentaries.

Simonides’ motives for spreading the false claim that he made Codex Sinaiticus may be a mystery till Judgment Day, but his guilt is not hidden at all. He was a well-educated charlatan, and his claims about Codex Sinaiticus were false, as Tischendorf, Tregelles, Bradshaw, Scrivener, Wright, and others, equipped with the skill to evaluate the evidence, and the wisdom to evaluate the accuser, have already made clear.

James Snapp is writing for all the Tischend-dupes. The ONLY one of those gentlemen who actually saw the two sections of the manuscript was .. Tischendorf.

The 2009 Codex Sinaiticus Project, which laid bare the colour tampering of the manuscript, precisely as charged and explained by Kallinikos c. 1863 (the colouring having taken place in the 1850s) really ends the charade. We have the beautiful BEFORE and AFTER evidence that simiply demolishes this stain upon New Testament Bible studies.

After that, additional evidences came forth in many directions, corroborating the exposure of the Tischendorf charade, which became a major part of the quest to make an alternative competitor to the Reformation Bible.

Steven Avery

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com