Steven Avery

Administrator

Found by David W. Daniels, when we were conferencing about the various accents and marks in early Matthew, that Skeat & Milne say were an embellishment attempt by scribe A.

CSP

https://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manu...lioNo=1&lid=en&quireNo=74&side=r&zoomSlider=0

Amazingly, the scribe connects Matthew 2:6:

Matthew 2:6

And thou Bethlehem, in the land of Juda,

art not the least among the princes of Juda:

for out of thee shall come a Governor,

that shall rule my people Israel.

with ISAIAH, not Micah! (In the vertical margin note.)

it might be Hoses not Isaiah, but it probably is Isaiah

Micah 5:2

But thou, Beth-lehem Ephratah,

though thou be little among the thousands of Judah,

yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel;

whose goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting.

And we have not seen any comments on this from the Sinaiticus scholars!

This is definitely not mentioned at all in Scrivener (who relied on Tischendorf) or Jongkind or Skeat.

==============================

This blunder is referenced in a recent (or forthcoming) paper by Charles Evan Hill.

Irenaeus, the Scribes, and the Scriptures. Papyrological and Theological Observations from P.Oxy. 405 (pre-pub. version)

Charles Evan Hill

https://www.academia.edu/10485335/I...bservations_from_P.Oxy._405_pre-pub._version_

Kirk marks prophecy

CSP

https://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manu...lioNo=1&lid=en&quireNo=74&side=r&zoomSlider=0

Amazingly, the scribe connects Matthew 2:6:

Matthew 2:6

And thou Bethlehem, in the land of Juda,

art not the least among the princes of Juda:

for out of thee shall come a Governor,

that shall rule my people Israel.

with ISAIAH, not Micah! (In the vertical margin note.)

it might be Hoses not Isaiah, but it probably is Isaiah

Micah 5:2

But thou, Beth-lehem Ephratah,

though thou be little among the thousands of Judah,

yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel;

whose goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting.

And we have not seen any comments on this from the Sinaiticus scholars!

This is definitely not mentioned at all in Scrivener (who relied on Tischendorf) or Jongkind or Skeat.

==============================

This blunder is referenced in a recent (or forthcoming) paper by Charles Evan Hill.

Irenaeus, the Scribes, and the Scriptures. Papyrological and Theological Observations from P.Oxy. 405 (pre-pub. version)

Charles Evan Hill

https://www.academia.edu/10485335/I...bservations_from_P.Oxy._405_pre-pub._version_

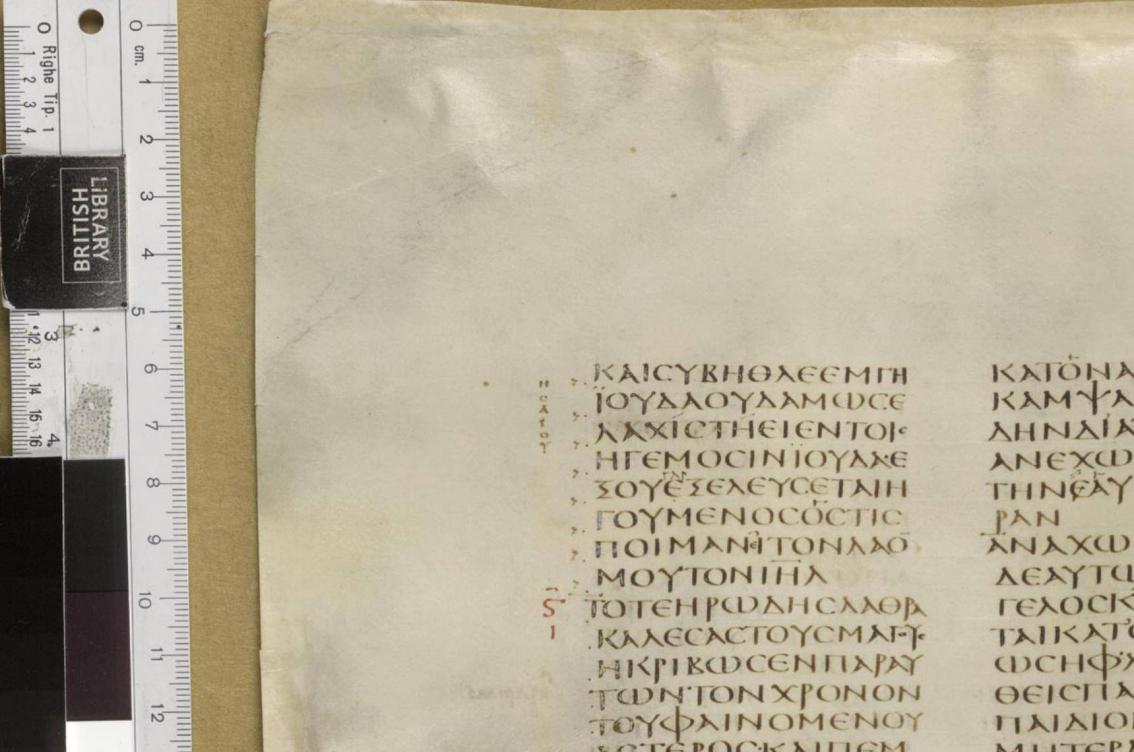

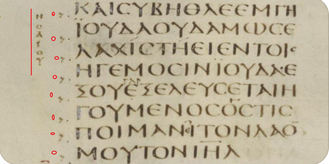

'This is confirmed by a look at the facsimile edition at, for instance. Matt. 2.6, citing Micah 5.1,3, where portions of the original ink show through in the letters next to the diplai and may be compared with the ink of the diplai. p.8

Illustration 4. Codex Sinaiticus (q. 74, f. lv), Matt. 2.6 citing Micah 5.2. Note scribal mistake in attribution to HCAIOY. What look like dots following the diplai are actually line pricks. p-10

Kirk marks prophecy

Last edited: