Steven Avery

Administrator

Robert Holcot - (1290c.-1349)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Holcot

VIAF

Exploring the boundaries of reason: three questions on the nature of God (1983)

Hester Goodenough Gelber (b. 1943)

https://books.google.com/books?id=h2VO_LRvorkC&pg=PA66

(quotes Lombard, Sentences)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Holcot

Robert Holcot, OP,[1] (c.1290-1349) was an English Dominican scholastic philosopher, theologian and influential Biblical scholar.

He was born in Holcot, Northamptonshire. A follower of William of Ockham, he was nicknamed the Doctor firmus et indefatigabilis, the "strong and tireless doctor." He made important contributions to semantics, the debate over God’s knowledge of future contingent events; discussions of predestination, grace and merit; and philosophical theology more generally.[2]

VIAF

Exploring the boundaries of reason: three questions on the nature of God (1983)

Hester Goodenough Gelber (b. 1943)

https://books.google.com/books?id=h2VO_LRvorkC&pg=PA66

(quotes Lombard, Sentences)

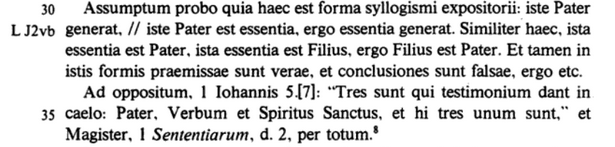

Assumptum probo quia haec est forma syllogismi expositorii: iste Pater generat, // iste Pater est essentia, ergo essentia generat. Similiter haec, ista essentia est Pater, ista essentia est Filius. ergo Filius est Pater. Et tamen in istis formis praemissae sunt verae. et conclusiones sunt falsae, ergo etc.

Ad oppositum, 1 Iohannis 5.(7]: “Tres sunt qui testimonium dant in caelo: Pater, Verbum et Spiritus Sanctus, et hi tres unum sunt," et Magister, 1 Sententiarum, d. 2, per totum.3

3 Peter Lombard. Sententiae 1.2. Spicilegium 1.2: 61. line 10 - 68. line 18.

https://books.google.com/books?id=h2VO_LRvorkC&pg=PA66

Last edited: