RGA - p. 138

The editions of the Vulgate produced at Wittenberg by Paul Eber (1564) and Paul Crellius (1574) omit the comma, consistent with the general suspicion towards this passage shown by the first two generations of Lutherans.163

163 Bludau, 1903a, 289; Posset, 1985, 248-251.

P. 144

But despite Paraeus’ calls for calm, Hunnius’ predictions turned out to have some foundation: the 1680 edition of

(Johannes) Crell’s Catechism for the Polish Socinian church contains an article on the spurious authority of the comma which concludes with what looks very much like a paraphrase of Calvin’s exposition.174

174 Crellius, 1680, 19: “Neque enim ex eo, quia tres isti testari dicuntur, protinus concludendum est, omnes illos esse personas, quandoquidem sequenti versiculo id ipsum de spiritu, aqua & sanguine dicitur, quod testentur: cum vero dicuntur unum esse, aut, ut alia exemplaria habent, in unum, non de alia unitate id intelligi debet, quam quæ testium solet esse in testimonio dicendo plane concordium, indicio est non solum quod de testibus hic agatur; sed etiam quod similiter in sequenti versiculo de spiritu, aqua & sanguine affirmetur, hos tres in unum esse, seu ut Latina versio sententiam recte expressit, unum esse.”

Crell, Johannes. Scriptura S. Trinitatis Revelatrix, Authore Hermanno Cingalio. Gouda: Jacobus

de Graef, 1678.

-----. Catechesis ecclesiarum Polonicarum, Unum Deum Patrem, illiusque Filium Unigenitum Jesum Christum, unà cum Spiritu Sancto; ex S. Scriptura confitentium. Primum anno M DC IX. in lucem emissa; & post earundem Ecclesiarum jussu correcta ac dimidia amplius parte aucta; atque per viros in his coetibus inclytos,

Johannem Crellium Francum, hinc Jonam Schlichtingium à Bukowiec, ut &

Martinum Ruarum, ac tandem Andream Wissowatium, recognita atque emendata: notisque cùm horum, tum & aliorum illustrata. Nunquam ante hac hoc modo edita. Stauropolis:

Philalethes, 1680.

p. 161

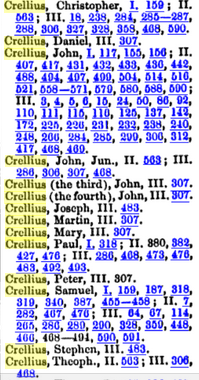

Johannes Crell (1590-1633)—head of the Socinian Academy at Raków, which would be shut down by the Polish crown four years after Crell’s death— used Erasmus’ Annotationes as evidence that the comma had crept into the text from the margin, and borrows Calvin’s argument that the original form of the comma in the Greek text refers to heavenly doctrine, redemption and truth rather

than to the orthodox conception of the Trinity, a notion to which Crell as a Socinian was opposed.24 Given the reservations that Socinians harboured about the comma, it is curious to note that Crell’s edition of the bible (1630) contains the comma, albeit marked off in distinct letters.25

24 Crell, 1678, 111.

25 Düsterdieck, 1852-1856, 2:356.

p. 205

Newton ... But it is important to note that he had actually read the works of several Socinians, including Sandius and

(Johannes or Samuel) Crell.)134

134 Snobelen, 2005, 271.

Snobelen, Stephen D. “Isaac Newton, heretic: the strategies of a Nicodemite.” BJHS 32 (1999): 381-419.

-----. “Isaac Newton, Socinianism and the ‘One Supreme God.’” In Socinianism and Arminianism: Antitrinitarians, Calvinists and Cultural Exchange in Seventeenth-Century Europe. Ed. Martin Mulsow and Jan Rohls. Leiden: Brill, 2005: 241-293.

Crell, Johannes. Scriptura S. Trinitatis Revelatrix, Authore Hermanno Cingalio. Gouda: Jacobus de Graef, 1678.

-----. Catechesis ecclesiarum Polonicarum, Unum Deum Patrem, illiusque Filium Unigenitum Jesum Christum, unà cum Spiritu Sancto; ex S. Scriptura confitentium. Primum anno M DC IX. in lucem emissa; & post earundem Ecclesiarum jussu correcta ac dimidia amplius parte aucta; atque per viros in his coetibus inclytos, Johannem Crellium Francum, hinc Jonam Schlichtingium à Bukowiec, ut & Martinum Ruarum, ac tandem Andream Wissowatium, recognita atque emendata: notisque cùmhorum, tum & aliorum illustrata. Nunquam ante hac hoc modo edita. Stauropolis:

Philalethes, 1680.

==================================

BCEME

p. 5

The first appearance of the term comma Iohanneum seems to be in Kortholt 1686 ... The term is attested sporadically over the next century: Wolf 1741, 5:311–313; Masch 1778–1790, 1:199 .... Other words and phrases used to describe the passage include ...versiculus (Bèze 1556, 318; Polanus von Polansdorff 1609, 1406; Crell 1680, 19)

p. 58

The editions of the Vulgate produced at Wittenberg by Paul Eber (1564) and

Paul Crell (1574) omit the comma, consistent with the general suspicion towards this passage shown by the first two generations of Lutherans.8

8 Bludau 1903a, 289; Posset 1985, 248–251.

p. 80

But despite Paraeus’ calls for calm, Hunnius’ predictions turned out to have some foundation: the 1680 edition of the catechism that

Johann Crell (1590–1633) wrote for the Socinian Academy at Raków contains an article on the spurious authority of the comma that

resembles Calvin’s exposition.40

40 Crell 1680, 19.

p. 104

Sozzini and his follower Johann Crell posited that those who live in civil society lay aside their natural rights to revenge wrongs, in exchange for the greater benefits of peace and civil order. This abrogation of rights is an act of choice and will that cannot be revoked.

p. 110-111

Consistent with the Socinian reservations about the comma,

(Johannes) Crell’s edition of the bible (1630) marks it off with brackets. In his preface, Crell stated that the comma does not occur in the oldest manuscripts and translations, was not mentioned by many Greek and Latin fathers, and was rejected by Luther and Bugenhagen as an interpolation.144

144 Crell and Stegmann 1630, †8v–††1r, 849–850; Düsterdieck 1852–1856, 2:356; Bludau 1904a, 289–290, 299–300.

p. 155

As to Alexandre’s assertion that only Socinians believed this passage to be an addition, Simon pointed out that

Crell’s edition actually includes the comma.

p. 160

Newton met the Transylvanian Unitarian Zsigmond Pálfi in 1701. In 1711 he met the Socinian Samuel Crell (1660–1747), grandson of Johann Crell and pastor of the church of the Polish Brethren. In 1726, Newton offered Samuel Crell financial support to publish a book on the prologue to the fourth gospel. Newton himself possessed at least ten Arian, Socinian and Unitarian works, including titles by John Biddle,

Johann Crell, Samuel Crell, György Enyedi, Stanisław Lubienicki, Christoph Sand, Jonasz Szlichting and Fausto Sozzini, besides works by his followers Samuel Clarke and William Whiston, which were probably presented as gifts.

p. 161

Newton

He also shared the Unitarians’ suspicion of the doctrine of the Incarnation.153

153 See Whiston 1727–1728, 2:1075; Whiston 1749–1750, 1:206 (Newton’s support of Arian and Baptist positions); Iliffe 1999 (Newton’s anti-Catholicism); Snobelen 1999, 383–390 (a careful comparison of Newton’s beliefs and those of the Socinians and Unitarians),

404 (Newton and Crell); Snobelen 2005a, 248–251, 266–267, 294–295

(Newton, Pálfi and Crell), 252–255, 296–298 (Newton’s heterodox library); Snobelen 2005b, 409; Buchwald and Feingold 2012, 433–434. On the distinctions between various Antitrinitarian groups in the later seventeenth century, see Mulsow 2005.

p. 203

This proposition was praised by John Jackson, who pointed out that this relative definition had implications for the nature of Christ’s divinity. Jackson noted that in the bible, ‘the Son is not call’d Jehova at all, in his own Person; or if He is, then the Name Jehova cannot mean so much as necessary Self-Existence, but something which may be Communicated.’327 Others, such as Edward Welchman and Daniel Waterland, found the proposition distinctly suspicious.328 One sharp-eyed critic, the Calvinist John Edwards, spotted that Clarke’s argument was borrowed from the treatise On God and his attributes (1630) by the

Socinian Johann Crell.329

This treatise was reprinted in the Bibliotheca fratrum Polonorum, a copy of which sat on Clarke’s shelves.330 Edwards also noticed that Newton had run the same argument in the general scholium to the new edition of his Principia, published in 1713.331

326 S. Clarke 1714b, 284; he emphasises this point at 290; cf. Snobelen 2001, 187.

327 Jackson 1714, 11, 26–27, 30–31 (Clarke’s reply), 32; cf. Snobelen 2001, 187.

328 Welchman 1714, 13; Waterland 1719, 47–72.

329 John Edwards 1714, 36; cf.

J. Crell, in Völkel 1630, 101: ‘[. . .] vox Dei tum in Hebraeo, tum in Graeco, ejusmodi adjectionem amat, quâ relatio ad alios significatur, ut cùm Deus dicitur esse Deus hujus aut illius; [. . .] Dei vox potestatis inprimis & imperii nomen est [. . .].’ Cf. Ferguson 1976, 77–78; Snobelen 2001, 192–194.

330 Snobelen 2001, 193–194.

331 Newton 1713, 482.

DEFINITION OF GOD

p. 204

Edwards was probably right in identifying

Crell as the immediate source, but in fact the notion appears

in nuce in the Racovian catechism, where the word ‘God’ is defined as denoting ‘him, who both in the heavens, and on the earth, doth so rule and exercise dominion over all, that he acknowledgeth no superior, and is so the Author and Principall of all things, as that he dependeth on none’.

p. 231

The exchange between Emlyn and Martin attracted attention from all over Europe. Samuel Crell mentioned it in a letter to La Croze.464

464 Samuel Crell to La Croze, 20 January 1718, in La Croze 1742–1746, 1:89–90; Bludau 1922, 138, misread the date of this letter as 1710. Crell published a study of 1 Jn 5 under the pseudonym

‘J. Philalethe’ in the Bibliothèque angloise for 1720.

p. 248

News of the discovery of Newton’s manuscript travelled quickly. Samuel Crell ordered a copy immediately, and on 28 September 1736 he sent news of its existence to William Whiston Jr, the son of Newton’s former protégé, attributing the loss of the pages at either end to Le Clerc’s negligence.541

541 Samuel Crell to Whiston Jr, Leicestershire Record Office, Conant MSS, DG11/DE.730/2 letter 123A, cit. Snobelen 2005b, 407–408 n. 134: ‘[. . .] adeo a Clerici negligenter habitas ut prioris initium alterius finis desit’. A copy of the copy ordered by Samuel Crell is extant in Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek ms Semin. Remonstr. Bibl. 12. Cf. Mandelbrote 2004, 108; Snobelen 2005a, 250 n. 48; Snobelen 2005b, 408 n. 135.

============

[Crell, Johann and Joachim Stegmann, trans.] Das Newe Testament, Das ist / Alle Bücher des newen Bundes / welchen Gott durch Christum mit den Raków: [Sternacius], 1630.

Crell, Johann. Catechesis ecclesiarum Polonicarum. Stauropolis [Amsterdam]: Eulogetus Philalethes [Christiaan Petzold?], 1680.

De Rossi, Johannes Franciscus Bernardus Maria. De tribus in caelo testibus, Patre, Verbo et Spiritu Sancto, qui tres unum sunt, I. Ep. Joan. Cap. V. ℣. 7. Dissertatio Adversus Samuelem Crellium, aliosque. Venice: Occhi, 1755.

‘Philalethe, J.’ [Samuel Crell]. ‘Explication de trois Passages de la Sainte Écriture, savoir Gen. III.17. & IV. 15. & 1 Jean V. 8.’ Bibliothèque angloise 7 (1720): 248–284.

Völkel, Johann. De vera religione libri quinque: quibus praefixus est Iohannis Crellii Franci liber De deo et eius attributis, ita ut unum cum illis opus constituat. Raków: Sternacius, 1630