Steven Avery

Administrator

Sancho Carranza de Miranda (d. 1531)

https://es-m-wikipedia-org.translat...tr_sl=es&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

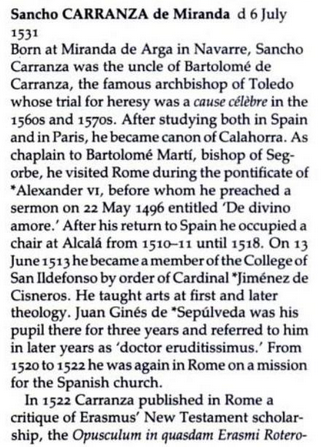

Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation, Volumes 1-3 (2003)

http://books.google.com/books?id=hruQ386SfFcC&pg=PA273

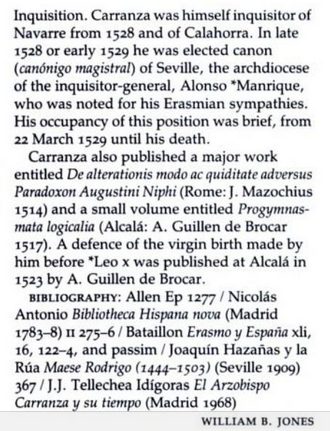

Sanctii Carranzae a Mirāda theologi Opusculum in quasdam Erasmi Roterodami annotationes (1522)

http://books.google.com/books?id=-MxdmAEACAAJ

https://es-m-wikipedia-org.translat...tr_sl=es&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

Sancho Carranza de Miranda, religious from Navarre from the 16th century, paternal uncle of Bartolomé de Carranza de Miranda.

He studied Philosophy and Theology at the Bologna College of the University of Paris , an institution where he also received his doctorate. He was canon of Calahorra and magisterial of Seville . He was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the University of Alcalá , having as epigones Martín de Azpilcueta and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda . Cisneros recruited for the university faculty members of the "Parisian group": Carranza, Antonio Ramírez de Villaescusa , Fernando de Encina and Domingo Soto , who introduced the renewal of logic.

In 1519 the anti-Erasmist controversy broke out in the Complutense cloister, started by Diego López de Estúñiga , with whom Carranza aligned himself. This transmitted to Erasmus an Opusculum in Desiderii Erasmi annotationes , which collated, from the scholastic, the translations of Erasmus, which he reputed could be of false Christological interpretation. Erasmus was not acquiescent with such comments and responded with Apologia de tribus locis quos ut recte taxatos ab Stunica defenderat Sanctius Carranza Theologus , a strong personal criticism against Carranza, whom he called "os impudens", and general against the Complutense cloister. The Spanish Church sent Carranza to Rome as a delegate to Leo X. Upon returning to Spain, he changed his opinion towards Erasmus, renouncing the previous diatribe that Estúñiga still maintained, becoming a passionate Erasmist.

Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation, Volumes 1-3 (2003)

http://books.google.com/books?id=hruQ386SfFcC&pg=PA273

Sanctii Carranzae a Mirāda theologi Opusculum in quasdam Erasmi Roterodami annotationes (1522)

http://books.google.com/books?id=-MxdmAEACAAJ

Last edited: